Bassem YoussefI was watching a news-of-the-week panel discussion program on BBC Arabic a few of weeks ago and the discussion turned to news of Bassem Youssef’s arrest by Egyptian authorities for insulting the president, denigrating Islam and undermining authority on his popular satirical TV show El Bernameg (البرنامج, The Program). In a case to whose fanfare Jon Stewert had added by discussing it in his own The Daily Show (Youssef had been scheduled to appear in court to face the stated charges, before the assigned judge dismissed the case) the topicality of satire in the Arab World was certainly given a potent shot in the arm.

Bassem YoussefI was watching a news-of-the-week panel discussion program on BBC Arabic a few of weeks ago and the discussion turned to news of Bassem Youssef’s arrest by Egyptian authorities for insulting the president, denigrating Islam and undermining authority on his popular satirical TV show El Bernameg (البرنامج, The Program). In a case to whose fanfare Jon Stewert had added by discussing it in his own The Daily Show (Youssef had been scheduled to appear in court to face the stated charges, before the assigned judge dismissed the case) the topicality of satire in the Arab World was certainly given a potent shot in the arm.

The discussion turned to the cultural prevalence and utility of satire as a medium of sociopolitical defiance when a panelist remarked that he had searched for a direct translation for satire in the Arabic dictionary and could not find one. Indeed, the term used most to refer to satire is sukhriyah (سخرية), which more accurately means sarcasm. And even though the Arabic literary tradition incorporates a form named Hija’ (هجاء) whose modes of function and purpose paralleled satirical literature in the English tradition, Hija’ was mostly, though not exclusively practiced in poetry1. Nevertheless, the panelist’s inference that Arabs had been collectively repressed so staunchly over the centuries, so as to have stripped them of the capacity to humorously mock while making pointed sociopolitical commentary hardly holds water for anybody who has grown up hearing endless mockery of Arab rulers and regimes. Words need not be written—or performed—to stand for culture.

Not that notable satirical Arabic works have not been written or performed. Syrian Dureid Lahham’s film Al-Hudoud (الحدود, The Border, 1987) is required viewing for any Arab cinema enthusiast and Kuwaiti Abdulhussain Abdulredha’s play Bye Bye London (1981) was watched in my home repeatedly when guests attended, so that the adults visiting could riff on the jokes and declare their keen interpretations of the meaning behind the punch lines.

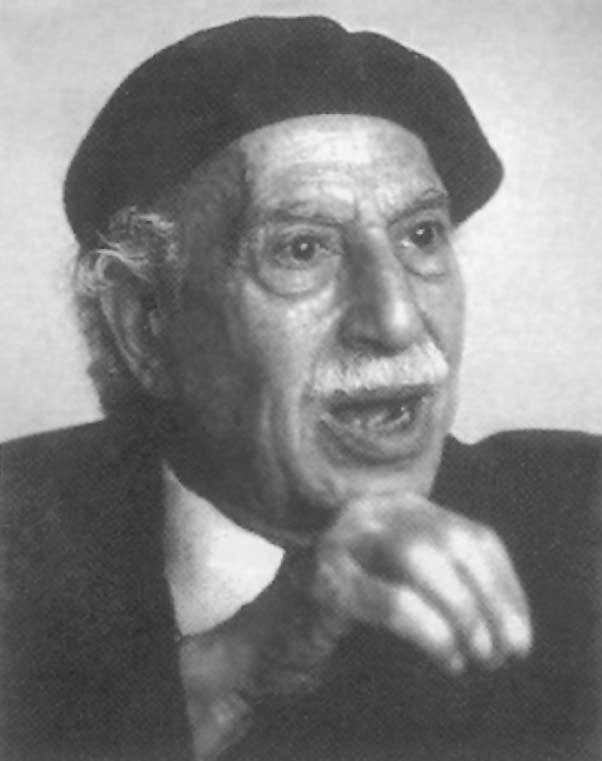

Tawfiq al-HakimDecades before these two works saw the light a satirical novel of the first order castigated the daylights out of the Egyptian government system. It was Diary of a Country Prosecutor (يوميات نائب في الأرياف), written by Tawfiq al-Hakim, one of the most important figures of 20th century Arab literature2. Al-Hakim is remembered primarily for his plays—he wrote around seventy full length plays—a few of which I read in my youth. I distinctly recall how impacted I was by al-Hakim’s Journey to Tomorrow (رحلة إلى الغد), a science fiction play ascribed to his theater of the mind ('théâtre des idées', المسرح الذهني) (which I’ve seen translated as intellectual theatre, a misleading translation, since the term refers to the destination of the works, their being written without intent to have them performed).

Tawfiq al-HakimDecades before these two works saw the light a satirical novel of the first order castigated the daylights out of the Egyptian government system. It was Diary of a Country Prosecutor (يوميات نائب في الأرياف), written by Tawfiq al-Hakim, one of the most important figures of 20th century Arab literature2. Al-Hakim is remembered primarily for his plays—he wrote around seventy full length plays—a few of which I read in my youth. I distinctly recall how impacted I was by al-Hakim’s Journey to Tomorrow (رحلة إلى الغد), a science fiction play ascribed to his theater of the mind ('théâtre des idées', المسرح الذهني) (which I’ve seen translated as intellectual theatre, a misleading translation, since the term refers to the destination of the works, their being written without intent to have them performed).

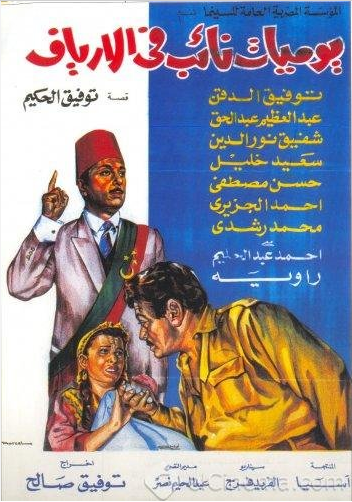

Diary of a Country Prosecutor (1969)Indeed, al-Hakim’s standing resides in his having ushered drama into the text of Arabic literature vividly and assertively. The prolific al-Hakim wrote more than plays, including philosophical and theological treatises, political essays, biographies, and novels the second of which Diary of a Country Prosecutor (1937) would be made into a film in a drastically different Egypt 32 years later.

Diary of a Country Prosecutor (1969)Indeed, al-Hakim’s standing resides in his having ushered drama into the text of Arabic literature vividly and assertively. The prolific al-Hakim wrote more than plays, including philosophical and theological treatises, political essays, biographies, and novels the second of which Diary of a Country Prosecutor (1937) would be made into a film in a drastically different Egypt 32 years later.

Tawfiq al-Hakim, who had been sent to France to pursue graduate studies in law, and had failed to earn a degree as he focused on cultural enrichment istead3, would fatefully land a post in the Egyptian countryside as a prosecutor4. By then, al-Hakim had begun writing and would find ample fodder in his prosecutorial experience.

Diary of a Country Prosecutor is such a formatively varied novel. It involves elements of folkloric storytelling, dramatic suspense, satire, and realism whereas its adapted screenplay folds the first three into the last, from a cinematic formative standpoint, toning down the satire to accommodate the censor in ways predictable and not. The film’s plot unfolds in an unnamed village in an unnamed year and involves many characters, most of whom are unnamed, including the Prosecutor, the protagonist, whose journal entries over the course of twelve days, October 11 to 22, tell the story. Storytelling through journal entries facilely justifies the use of first person if nothing else and the paucity of names… Well, perhaps such details don’t mean that much when one is as jaded as the Prosecutor and besides, who needs names when titles will do.

The ProsecutorThe Prosecutor is awakened in the middle of the first night to attend the scene of a shooting in a distant marsh. Upon arrival with his prosecutorial team along with the Sherriff and his team, the Prosecutor is proud to demonstrate the meticulousness of his method in assessing the crime scene and in questioning the shooting victim, who shockingly was left to suffer in the scene of the attack by the constable to first arrive upon the scene, while the latter waited for the crime investigation unit to arrive! Ahem, but the prosecutor’s meticulousness has nothing to do with his commitment to fulfilling the cause of justice, rather with a compultion to shield himself from any criticism from his higher-ups. He admonishes his assistant to fulfill all bureaucratic expectations, recalling an occasion when he himself had been chastised by a superior for submitting a dossier on a murder case that was too light—too physically light.

The ProsecutorThe Prosecutor is awakened in the middle of the first night to attend the scene of a shooting in a distant marsh. Upon arrival with his prosecutorial team along with the Sherriff and his team, the Prosecutor is proud to demonstrate the meticulousness of his method in assessing the crime scene and in questioning the shooting victim, who shockingly was left to suffer in the scene of the attack by the constable to first arrive upon the scene, while the latter waited for the crime investigation unit to arrive! Ahem, but the prosecutor’s meticulousness has nothing to do with his commitment to fulfilling the cause of justice, rather with a compultion to shield himself from any criticism from his higher-ups. He admonishes his assistant to fulfill all bureaucratic expectations, recalling an occasion when he himself had been chastised by a superior for submitting a dossier on a murder case that was too light—too physically light.

Among the rewards of Diary is that the whodunit turns out merely a vehicle for sustained reading. The shooting investigation acts as an exposition of much rot in government: in the judicial, police, and electoral systems. The problem of the prosecutor’s jadedness is uncorrectable just as the murder case is unsolvable, not that they couldn’t be. Oh, but where does a lone country prosecutor begin to mend the rot … He doesn’t.

Diary the film preserves much of the story, not surprising since with a 150-page novel adapted for a near 2-hr film, little abridging was necessary if one considered that the typical manifestation rate of a screenplay is a minute in film per page. At least one macabre scene is omitted, since it likely could not have been filmable in Egypt at the time, one involving crime scene brain extraction and a frivolous, grotesque shared search for a deadly bullet.

The Sheriff, making a persuasive case Tawfiq Saleh, director of Diary, is one whose work I have long admired and whose best film The Dupes I elected to discuss in launching this blog. Saleh worked on Diary’s screenplay as he did on most of his films’, which leaves me mulling how concerned he was about potential trouble with the censor. As I had noted in my extended review of The Dupes, Diary of a Country Prosecutor was reportedly banned by the censor until Nasser himself permitted its release in full. I now suspect this account is apocryphal. What I did not know when I wrote that review over a year ago is the extent of Nasser’s admiration for al-Hakim, particularly Hakim’s Return of the Soul (عودة الروح, his first novel)5. Moreover, having read the book since, I have noted that the film’s very last shot depicts the prosecutor scribing his final journal note: “22 October 1935.” Not only did the novel not end in such a fashion, but the deliberate insertion of the year of the story in the pivotal final frame of the film suggests the extent to which the screenplay writers were concerned about having the film construed as an unsuccessfully veiled attack on the Nasser regime.

The Sheriff, making a persuasive case Tawfiq Saleh, director of Diary, is one whose work I have long admired and whose best film The Dupes I elected to discuss in launching this blog. Saleh worked on Diary’s screenplay as he did on most of his films’, which leaves me mulling how concerned he was about potential trouble with the censor. As I had noted in my extended review of The Dupes, Diary of a Country Prosecutor was reportedly banned by the censor until Nasser himself permitted its release in full. I now suspect this account is apocryphal. What I did not know when I wrote that review over a year ago is the extent of Nasser’s admiration for al-Hakim, particularly Hakim’s Return of the Soul (عودة الروح, his first novel)5. Moreover, having read the book since, I have noted that the film’s very last shot depicts the prosecutor scribing his final journal note: “22 October 1935.” Not only did the novel not end in such a fashion, but the deliberate insertion of the year of the story in the pivotal final frame of the film suggests the extent to which the screenplay writers were concerned about having the film construed as an unsuccessfully veiled attack on the Nasser regime.

Diary’s principle participants are competent but not particularly enthralling. Tawfiq ad-Daqn is his vivid self as the Sherriff and Abdul’athim Abdulhaq is convincingly queer as the mystic-cum-village-crazy Sheikh ‘Asfour. The lead role is performed adroitly with coy restraint by the versatile, underappreciated actor Ahmed Abdulhalim. The staging is mannered in the studio-bound sense and the action lacking the élan evident in Saleh’s The Dupes, for example, and this despite a few elaborately staged shots, each over half a minute long.

By Diary’s end, I realized what I didn’t when I referred to the film in my blog’s very first post, over a year ago, that the film’s excellence lies in its source material. I learned what I’ve heard and read from so many film practitioners over the years: “It’s in the script."

Notes:

1. Van Gelder, Geert Jan. The Bad and the Ugly: Attitudes towards Invective Poetry (Hija) in Classical Arabic Literature. Brill: E.J., 1988. Print. PP. 2

2. Allen, Roger M. A. An Introduction to Arabic Literature. N.p.: Cambridge University Press, 2000. N. pag. Web.

3. See sourse # 2

4. Johnson-Davies, Denys, ed. The Essential Tawfiq al-Hakim: Plays, Fiction, Autobiography. Cairo: The American University in Cairo Press, 2008. Print. PP. 3

5. Mondal, Anshuman A. Nationalism and Post-Colonial Identity: Culture and Ideology in India and Egypt. London: Routledge, 2003. Print. PP 199

*Diary of a Country Prosecutor the novel has been translated into English.