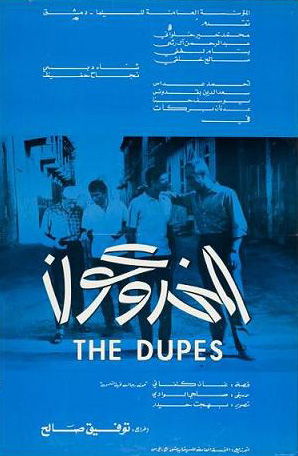

The Dupes (1972): Forgotten Masterpiece of Arab Cinema

03-1-2012 | tagged

03-1-2012 | tagged  1972,

1972,  Ghassan Kanafani,

Ghassan Kanafani,  Palestinian,

Palestinian,  Tawfiq Saleh,

Tawfiq Saleh,  The Deceived,

The Deceived,  The Duped,

The Duped,  The Dupes,

The Dupes,  The Wages of Fear,

The Wages of Fear,  المخدوعون |

المخدوعون |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |  Email Article |

Email Article |  The Dupes (1972)A haggard man in extreme longshot lumbers over desert sands toward the viewer. A human skeleton foregrounds the shot. “Aghh, hackneyed symbolism of danger and morbidity,” I thought to myself. Upon reflection, I realize that there was nothing hackneyed about such symbolism, because it was not facile but apt. Metaphor is integral to narrative films that wish to affirm a point of view while avoiding didacticism. Metaphor will have manifested effectively when we decide that a film “has meaning.” Yet, most films’ metaphors fall short of delivering on their ostensible promise to inculcate us in the lessons about the world to which they point.

The Dupes (1972)A haggard man in extreme longshot lumbers over desert sands toward the viewer. A human skeleton foregrounds the shot. “Aghh, hackneyed symbolism of danger and morbidity,” I thought to myself. Upon reflection, I realize that there was nothing hackneyed about such symbolism, because it was not facile but apt. Metaphor is integral to narrative films that wish to affirm a point of view while avoiding didacticism. Metaphor will have manifested effectively when we decide that a film “has meaning.” Yet, most films’ metaphors fall short of delivering on their ostensible promise to inculcate us in the lessons about the world to which they point.

In The Dupes (المخدوعون, also The Duped and The Deceived), the struggles of the film’s four leads are both representative and metaphoric of the modern experience of the Palestinian people. It is precisely because The Dupes delivers as representation and as metaphor that it works; it is fine allegory. The Dupes draws a dramatic landscape that is poignant and credible in the realistic personal struggles of the main characters, drawn over space and time, while the metaphor grows the film’s audience entangling tentacles of anguish, horror and morbidity, whose marks well outlast The Dupes’ uncompromising ending.

As Viola Shafiq remarks in her book Arab Cinema, The Dupes is a Pan-Arabist film par excellence1 (though the adapted story of the film is anything but Pan-Arabist): a Syrian state production directed by Egyptian Tawfiq Saleh whose screenplay is based on the novella Men in the Sun by venerated Palestinian literary figure Ghassan Kanafani. Alignment of the principles’ interests may explain the film’s cohesiveness, its integrality. Syria’s National Film Organization in 1972 was interested in stories of class oppression, because such stories were constituent to the school of social realism that a professedly socialist (a constitutionally secular socialist state) government sanctioned. It was also interested in stories about Palestinian struggle, an extension of the state’s broadcast and much trumpeted support and sponsorship of Palestinian resistance. The National Film Organization’s site indicates that of the sixteen films produced by it during the 1970s, six related topically to the Palestinian experience. Also notable is that fourteen of the sixteen credited the director as screenwriter (In most cases, such is in the case of The Dupes, the director was the sole credited screenwriter.)2

Ghassan KanafaniGhassan Kanafani was himself a Palestinian refugee. Although he spent most of his boyhood in Yafa (Java), he was born in Akka (Aker) in 1936 and it was from Akka that he and his family fled Palestine, after the first attack on the city, in April of 1948. The family eventually settled in Damascus where he became involved with the Arab Nationalist Movement (ANM), upon his introduction to the group’s founder George Habash, who would exert a marked influence over the development of Kanafani’s own ideas of resistance, liberation, and self-determination for the Palestinian people. In 1955, Kanafani moved to Kuwait, a location that would figure mightily in Men in the Sun. In 1962, having moved to Beirut, Kanafani wrote the operative novella, his first. Its staunch repudiation of escapism and call for self-reliance foresaw the disappointment and dejection in Nasserism/Pan-Arabism, after the ignominious defeat of the 1967 War. Indeed, Habash would found the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) that very year and Kanafani would two years later found the organization’s publication Al-Hadaf in Beirut, for which he served as editor until his assassination in 1972 by a car bomb, near certainly planted by the Mossad3. Kanafani did watch The Dupes, released earlier that year, according to Salem who reports having freighted a copy of the film personally by car, from Damascus to Beirut.4

Ghassan KanafaniGhassan Kanafani was himself a Palestinian refugee. Although he spent most of his boyhood in Yafa (Java), he was born in Akka (Aker) in 1936 and it was from Akka that he and his family fled Palestine, after the first attack on the city, in April of 1948. The family eventually settled in Damascus where he became involved with the Arab Nationalist Movement (ANM), upon his introduction to the group’s founder George Habash, who would exert a marked influence over the development of Kanafani’s own ideas of resistance, liberation, and self-determination for the Palestinian people. In 1955, Kanafani moved to Kuwait, a location that would figure mightily in Men in the Sun. In 1962, having moved to Beirut, Kanafani wrote the operative novella, his first. Its staunch repudiation of escapism and call for self-reliance foresaw the disappointment and dejection in Nasserism/Pan-Arabism, after the ignominious defeat of the 1967 War. Indeed, Habash would found the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) that very year and Kanafani would two years later found the organization’s publication Al-Hadaf in Beirut, for which he served as editor until his assassination in 1972 by a car bomb, near certainly planted by the Mossad3. Kanafani did watch The Dupes, released earlier that year, according to Salem who reports having freighted a copy of the film personally by car, from Damascus to Beirut.4

Tawfiq SalehIf Kanafani’s productivity had been cut short by his death then so was Tawfiq Saleh’s—by career death. In total, Saleh directed a mere seven narrative features between the years of 1955 and 1980, of which I have seen five. Saleh had made his narrative feature debut with Fools’ Alley, a film whose screenplay he had co-written with Najib Mahfouz, a film whose ironic realism was admired, though not at the box office.4 According to Saleh, it was his second film that won him the admiration of Nasser himself, who upon watching Struggle of the Heroes, had suddenly agreed to nationalize the film industry, having publicly resisted for three years. The second time Nasser would bear upon a film of Saleh’s the latter had already grown wary of Nasser’s regime, not least because the film in question, his fifth Diary of a Country Prosecutor (which I aim to write about soon), one of five on whose scripts he would work over the course of his career, was shot in 1968, in the wake of the startling and deflating defeat of Egypt in the 1967 War. According to Saleh, the film’s release had been held up by the minister of interior, who had formed a committee to look into which content ought be censored. Then, upon learning of this and having seemingly watched Diary, Nasser insisted that the film be released in full.5

Tawfiq SalehIf Kanafani’s productivity had been cut short by his death then so was Tawfiq Saleh’s—by career death. In total, Saleh directed a mere seven narrative features between the years of 1955 and 1980, of which I have seen five. Saleh had made his narrative feature debut with Fools’ Alley, a film whose screenplay he had co-written with Najib Mahfouz, a film whose ironic realism was admired, though not at the box office.4 According to Saleh, it was his second film that won him the admiration of Nasser himself, who upon watching Struggle of the Heroes, had suddenly agreed to nationalize the film industry, having publicly resisted for three years. The second time Nasser would bear upon a film of Saleh’s the latter had already grown wary of Nasser’s regime, not least because the film in question, his fifth Diary of a Country Prosecutor (which I aim to write about soon), one of five on whose scripts he would work over the course of his career, was shot in 1968, in the wake of the startling and deflating defeat of Egypt in the 1967 War. According to Saleh, the film’s release had been held up by the minister of interior, who had formed a committee to look into which content ought be censored. Then, upon learning of this and having seemingly watched Diary, Nasser insisted that the film be released in full.5

Saleh’s exasperation came to a head with the censoring and criticism of his fourth film Mister Balti, shot in 1967, but released in ’68, the same year as Diary. Salem took offense and soon thereafter, having had his proposal to make a film based on Men in the Sun rejected by the Egyptian General Organization (the state operated TV, radio and film production outfit), proposed the project to Syria’s National Film Organization. Saleh must have noted the suitability of his proposed project to the production interests of the Organization, considering the organization’s putatively nationalist, social realist persuasion, officially dubbed Alternative Cinema. He would make one more film, an Iraqi state production dubbed Long Days, in 1980. Soon thereafter, Saleh returned to Egypt where he still lives in Cairo.6

The Dupes is exceedingly faithful to the novella, except in two ways that I will later dwell on. Like the novella, the film is formed in two parts, the first involves the background of three impoverished Palestinians, readily representative of three generations of refugees, who journey from their diaspora communities (refugee camps in the case of at least two) to Shatt al-Arab in southern Iraq, with the intention of getting smuggled into nearby Kuwait, where they hope to locate work and opportunity to alley the various conditions of desperation they aspire to overcome. These backstories are presented convincingly, as memories being recalled by triggers, mostly during dialogue with the head of a an Iraqi smuggling outfit that all three men visit before deciding to take the risk of their lives in being smuggled in a water truck, driven by a soliciting competitor to the Iraqi smuggler, a Palestinian expat named Abul-khaizaran. The men do not choose Abul-khaizaran because he's Palestinian, but because his rate is ten dinars each, five less than that of his competitor.

The Dupes (1972)

The Dupes (1972) The Wages of Fear (1953)

The Wages of Fear (1953)

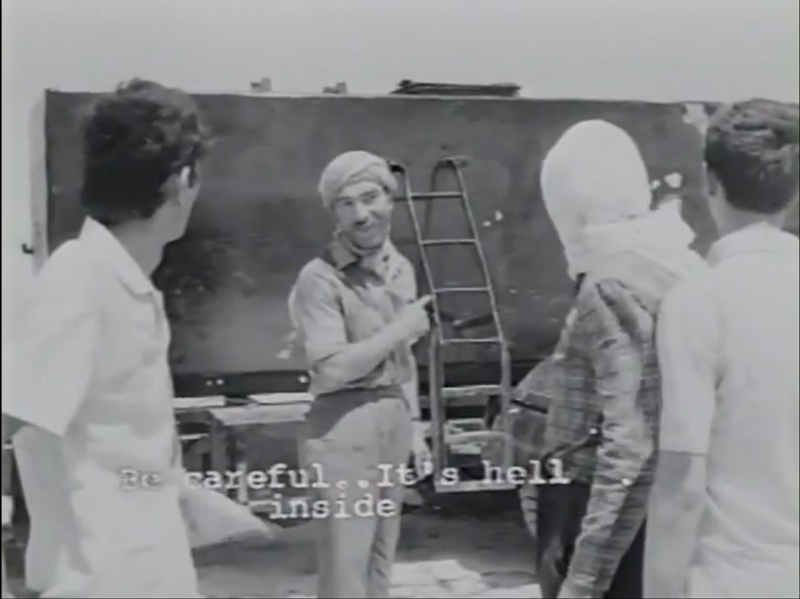

The second part (about half) of the film involves the smuggling adventure. The three men (I hesitate for a moment to call sixteen year-old Marwan a man) agree to be smuggled by Abul-khaizaran in the tank of the water truck that he must drive back to its owner, his employer, in Kuwait. This second part does tell Abul-khaizaran’s story, but mainly focuses on the hellish experience of Abu Qais, As’ad and Marwan, intermittently hiding in the suffocating water tank, smoldering in the August sun. It is in this second half, mostly linear narrative driven, that Saleh’s compositional mastery shines. In their blindingly bright starkness, the images of the wretched smuggled and the equally doomed Abul-khaizaran on a decrepit capsule rolling the sands of hell have haunted me. The suspense generated by the adventure, whose participants I had come to care about, edited expertly by Saheb Haddad, engaged me thoroughly. Soon after the men embarked on their perilous journey, I recalled the frenzied and futile adventure in Clouzot’s masterpiece The Wages of Fear. If Saleh hadn’t been inspired by it then it must have been because he had not seen it. Saleh had concluded his stay in France at the end of 1953, year of the French thriller’s release.7

The Dupes (1972)

The Dupes (1972) The Wages of Fear (1953)If there is an advantage to watching The Dupes in its current deteriorated state of photography and sound (it begs for restoration more than any other Arab film I’ve seen), it is the relative agreement between live action and archival still footage in a montage of the two early in the film. This montage mostly depicts Palestinian displacement then settlement in refugee camps in 1948, the Nakba into which hundreds of thousands of Palestinians had been plunged (or had plunged, as Kanafani might have preferred to see it), accompanied by a mournful expository narration. This review of Palestinian modern history does not exist in the novella, and considering that the footage depicts Farouq I of Egypt, Abdul-Aziz bin Saud of Saudi Arabia and multiple Hashemite monarchs, as the accompanying narration turns to decrying the treachery of Arab regimes, I wondered if this montage may have well been the only condition that the National Film Organization had attached to the production. Expectedly, the brazen accusations of betraying the Palestinian people would limit the film’s exposure, which Saleh has since lamented, expressing that The Dupes was the film that had marked his maturation as a director.8 Tawfiq Saleh may have known that his film would speak for a regime as self-serving and oppressive as the one he had escaped, but at least the Syrians didn’t tacitly require installation of a couple of song and dance numbers, which appear in all four Egyptian films of his that I have seen, including inexplicably in the one that had escaped the censor’s scissors—Diary of a Country Prosecutor. They also (spoiler alert) didn’t require the harrowing ending be altered to something more hopeful than written. The ending, in fact, involves the second marked departure from the novella.

The Wages of Fear (1953)If there is an advantage to watching The Dupes in its current deteriorated state of photography and sound (it begs for restoration more than any other Arab film I’ve seen), it is the relative agreement between live action and archival still footage in a montage of the two early in the film. This montage mostly depicts Palestinian displacement then settlement in refugee camps in 1948, the Nakba into which hundreds of thousands of Palestinians had been plunged (or had plunged, as Kanafani might have preferred to see it), accompanied by a mournful expository narration. This review of Palestinian modern history does not exist in the novella, and considering that the footage depicts Farouq I of Egypt, Abdul-Aziz bin Saud of Saudi Arabia and multiple Hashemite monarchs, as the accompanying narration turns to decrying the treachery of Arab regimes, I wondered if this montage may have well been the only condition that the National Film Organization had attached to the production. Expectedly, the brazen accusations of betraying the Palestinian people would limit the film’s exposure, which Saleh has since lamented, expressing that The Dupes was the film that had marked his maturation as a director.8 Tawfiq Saleh may have known that his film would speak for a regime as self-serving and oppressive as the one he had escaped, but at least the Syrians didn’t tacitly require installation of a couple of song and dance numbers, which appear in all four Egyptian films of his that I have seen, including inexplicably in the one that had escaped the censor’s scissors—Diary of a Country Prosecutor. They also (spoiler alert) didn’t require the harrowing ending be altered to something more hopeful than written. The ending, in fact, involves the second marked departure from the novella.

The Dupes (1972)

The Dupes (1972) The Wages of Fear (1953)Allegorical themes in Men in the Sun, which I have read, are mostly preserved in The Dupes: complicity and treachery of Arabs, including Palestinians themselves, against Palestinian liberation and self-determination; the futility of escapism and the imperative to stand to aggression through conscious and active resistance; the loss of land as tantamount to the loss of manhood; and the championing of secular resistance. Yet, other than the interpolation of the facile and manipulative montage discussed earlier, Saleh altered the novella’s ending, (spoiler alert) wherein Kanafani mentions nothing of a struggle by the characters in the tank against the murderous heat that the three had to endure. Having dispensed of the men’s bodies at a rubbish collection location then redoubled to take their valuables, Kanafani ends the novella by having an overwrought Abul-khaizaran repeatedly cry, “Why didn’t you bang on the walls?”

The Wages of Fear (1953)Allegorical themes in Men in the Sun, which I have read, are mostly preserved in The Dupes: complicity and treachery of Arabs, including Palestinians themselves, against Palestinian liberation and self-determination; the futility of escapism and the imperative to stand to aggression through conscious and active resistance; the loss of land as tantamount to the loss of manhood; and the championing of secular resistance. Yet, other than the interpolation of the facile and manipulative montage discussed earlier, Saleh altered the novella’s ending, (spoiler alert) wherein Kanafani mentions nothing of a struggle by the characters in the tank against the murderous heat that the three had to endure. Having dispensed of the men’s bodies at a rubbish collection location then redoubled to take their valuables, Kanafani ends the novella by having an overwrought Abul-khaizaran repeatedly cry, “Why didn’t you bang on the walls?”

Addressing the alteration to the ending, Saleh has remarked that Kanafani in his novella is saying that the people in the tank die without resisting.9 In the film, because of Saleh’s seeming disapproval of Kanafani’s fatalism, sounds of banging against the walls of the tank are heard, while Abul-khaizaran pleads and cajoles a Kuwaiti customs agent to stamp his papers. Moreover, Saleh makes the last shot of the film one of a stiff extended hand curled as if to knock.

I disagree with Saleh’s assumption that Kanafani denied his characters the will to resist. Just because something is not depicted in the plot, doesn’t mean it didn’t happen in the story. I qualify that Kanafani wouldn’t have cared to portray resistance from the characters in the tank, because he would have deemed their resistance at that point not merely futile, but inconsequential. As far as Kanafani was concerned, the three characters’ lives and their will to resist had been doomed as soon as they had signed up to escape their realities as landless refugees and their imperative to resist.

The much debated discrepancy in the endings of the two works notwithstanding; there is evident parallelism between the lives of Kanafani and Saleh. Yet, what is special about The Dupes is that this parallelism between the lives of author and director, notable as it is, is surpassed in the pathos of the parallelism between the lives of Saleh and the principal characters in his film. In an interview several years ago, Saleh lamented not having been able to work in Egypt since his return from Iraq in the early 80s: “Perpetually, I am a stranger, a stranger and this is my fate … I mean that I am in a society of which I approve, but which doesn’t approve of me. What do you do?”10 If Saleh’s career has been doomed because he is a stranger in his own society then the characters in The Duped are doomed because they are compelled to live as strangers in societies to which they could never belong.

*The Dupes is available in the US through Arab Film Distribution.

The Dupes (1972)

The Dupes (1972) The Wages of Fear (1953)

The Wages of Fear (1953)

Words Cited

1. Shafik, Viola. Arab Cinema: History and Cultural Identity. New York: The American University in Cairo Press, 1998. 155. Print.

2. The General Organization for Cinema. The National Film Organization, 2012. Web. 22 Feb. 2012. <http://www.cinemasy.com/en>.

3. Kanafani, Adnan. Ghassan Kanafani: Pages Were Turned (in Arabic). 3rd ed. N.p.: Ghassan Kanafani Cultural Institute, 2001. N. pag. Adnan Kanafani's Website. Web. 23 Feb. 2012.<http://adnan-ka.com/modules/publisher/item.php?itemid=146>.

4. Ibrahim, Bashar. "Ghassan Kanafani ... Cinematically." Al-Kuwait Magazine. Al-Kuwait Magazine, 25 July 2010. Web. 23 Feb. 2012. <http://www.kuwaitmag.com/index.jsp?inc=5&id=11543&pid=1620&version=121>.

5. "Tawfiq Saleh: The Cinema and the Failures of the Egyptian Revolution (in Arabic)." Al-Jazeera. Al-Jazeera, 26 May 2006. Web. 23 Feb. 2012. <http://www.aljazeera.net/NR/exeres/BBAA5CCD-8718-416C-B7F0 D0E68F025C32.htm>.

6. Saleh, Tawfiq. "Tawfiq Saleh to [Al-Jazeera] Documentary: My Most Significant Films Are Without a Screenplay (in Arabic)." Interview by Samira Mazahi. Al-Jazeera Documentary. Al-Jazeera Documentary, 26 Jan. 2009. Web. 23 Feb. 2012. <http://doc.aljazeera.net/followup/2009/01/ 2009122104148533299.html>.

7. D Weefi, Mohsen. The Cinema of Tawfiq Saleh (in Arabic). N.p.: The Cultural Development Fund, [c. 1998]. Digital Assets Repository. Web. 23 Feb. 2012. <http://dar.bibalex.org/webpages/mainpage.jsf?PID=DAF-Job:71860&q=>.

8. See reference # 5

9. See reference # 5

10. See reference # 5

Reader Comments