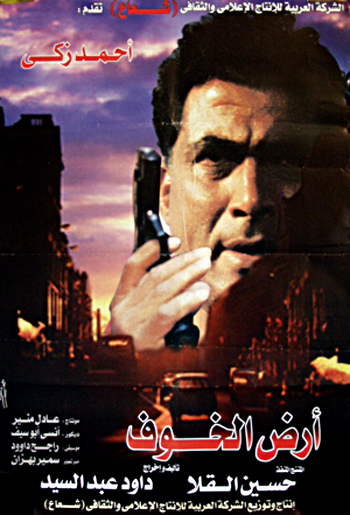

Land of Fear (1999): Life Under Deep, Interminable Cover

04-16-2014 | tagged

04-16-2014 | tagged  Ahmed Zaki,

Ahmed Zaki,  Daoud Abdel Sayed,

Daoud Abdel Sayed,  Egyptian film,

Egyptian film,  Land of Fear,

Land of Fear,  crime,

crime,  gangster,

gangster,  أحمد زكي,

أحمد زكي,  أرض الخوف,

أرض الخوف,  داوود عبدالسيد |

داوود عبدالسيد |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |  Email Article |

Email Article | Dear readers,

I had promised to review Land of Fear nearly two years ago, within my review of Daoud Abdel Sayed's Al-Kit Kat. Please refer to that review for more on Abdel Sayed's career. It remains inexplicable that Abdel Sayed's films, including Land of Fear, are not distributed widely. Perhaps I ought to do something about that...

There’s something about Daoud Abdel Sayed that gets to me. For years I thought it was his thoroughgoing, uncompromising approach to filmmaking or his films’ evident, grinning mischief. Now I realize that it’s more personal than that. I, like Abdel Sayed, have felt in my work an innate compulsion to prod, poke, and provoke as if to insist on disrupting conformity within nation-state societies that have left me—the eldest to Palestinian refugees—alienated, much like the characters that Abdel Sayed has continually depicted, characters whose lives represent society’s contradictions.

There’s something about Daoud Abdel Sayed that gets to me. For years I thought it was his thoroughgoing, uncompromising approach to filmmaking or his films’ evident, grinning mischief. Now I realize that it’s more personal than that. I, like Abdel Sayed, have felt in my work an innate compulsion to prod, poke, and provoke as if to insist on disrupting conformity within nation-state societies that have left me—the eldest to Palestinian refugees—alienated, much like the characters that Abdel Sayed has continually depicted, characters whose lives represent society’s contradictions.

Could I also be alienated like Abdel Sayed himself? Abdel Sayed, who has never declared being Coptic (Mustafa) in anything I have read or heard, in October of last year remarked, “As far as I am concerned, what is frightening about the current condition is that I have terrorism. At the same time that I have terrorism in the sense of explosions and murder and so on, from the other side I have intellectual terrorism, as in McCarthyism … And this is what is frightening me, that we have found ourselves, that I have found myself between two forces: one that wants to kill me and one that wants to silence me. “ (Abdel Sayed)

For years, I have felt a guilty pleasure in relishing crime pictures. There are vociferous anti-genre voices in cinephile circles, voices that suggest that genre films are commercial, that genre films are lowbrow and that genre films target the undiscerning, unless, of course, they happen to be made by Hitchcock or Ford or a French New Wave director. Only that I’m not bonkers about westerns or war films or romantic comedies or sci-fi films the same way I am about crime films. For years, I thought this had to do with the high moral stakes of their stories and charged emotional states of their characters, but I now know that there’s more. As Palestinian American poet would put it:

“i have always loved

criminals and not only the thugged

out bravado of rap videos and champagne

popping hustlers but my father

born an arab baby boy

on the forced way out

of his homeland his mother exiled

and pregnant gave birth in a camp” (Hammad)

Land of Fear (أرض الخوف) observes what its criminals do intently and keenly, but it stands out because it so handily explores what being a criminal means, not only for oneself, but for society. If I’ve made Land of Fear sound like a lofty treatise, well, that’s because it is. But it is also a suspenseful mood piece of a high order, the greatest Egyptian crime picture of all.

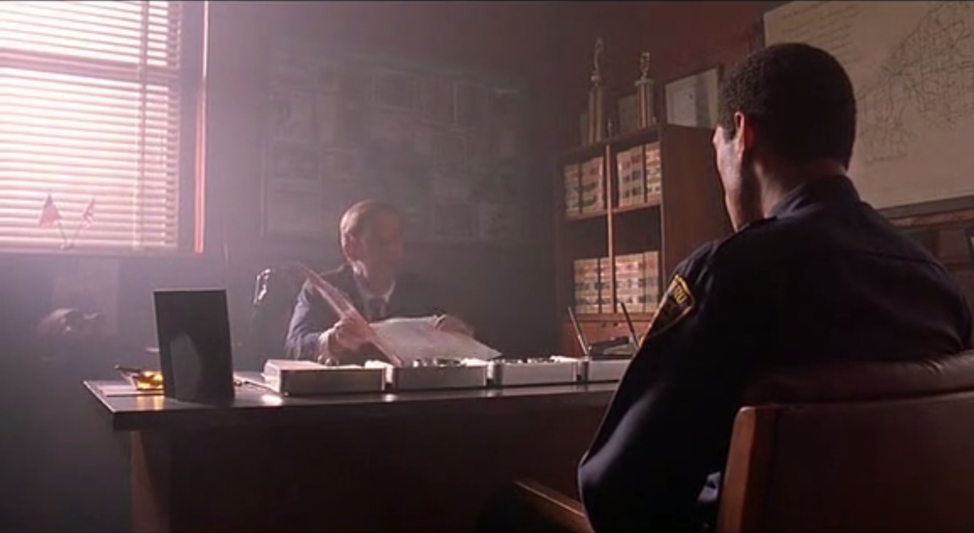

Russel (Lawrence Fishburn) is assigned to Deep Cover (1992)

Russel (Lawrence Fishburn) is assigned to Deep Cover (1992) Yahya is assigned to Land of Fear

Yahya is assigned to Land of Fear

Land of Fear stands for the title of the indefinite investigative operation to which a bright and incorruptible police officer Yahya al-Manqabawi (Ahmed Zaki) agrees to be assigned. Land of Fear is not your typical detail. It would position Officer Yahya to accept a bribe so that he may be arrested, convicted, dishonorably discharged then imprisoned, wherein he transforms into Yaha Abu-Dabbourah. Upon release, Yahya may begin his assignment to infiltrate the “underworld” (literal translation of the term used by Yahya--العالم السفلي) first as a smalltime hustler and drug dealer. Land of Fear is a lifetime assignment Yahya is told at the outset. He is to ambitiously pursue a career as a drug dealer with full immunity against any illegal actions he may take in pursuit of such a career; he is to operate with minimal oversight. The only proof of service being the reports he is to regularly submit, under the nom de plume Adam. Otherwise, a safety deposit box bound, failsafe document, signed by “people at the very top” guarantees the noted immunity, if his cover is ever blown or if Land of Fear unravels. He is told that nothing about Land of Fear is to be recorded other than in the failsafe document and that knowledge of the operation’s existence is to be passed orally from ministers of interior and justice and chief of intelligence onto their successors.

As Yahya’s station rises, from pool hall manager, to bodyguard, to cabaret manager—erstwhile moving increasing product—so does his star in the underworld. Yet, on the way to becoming one of Cario’s kingpins, spanning the decade of the 1970s, Yahya reports with increasing distress about the dissonance he experiences in leading a double life, especially with the passing and resigning of successive ministers and intelligence chiefs, who would have been privy to the Land of Fear operation. Such is his torment that he visits the location of the safety deposit box of note, more than to assure himself that the failsafe contract exists, but to assure himself that Land of Fear had not been a fabrication of his memory. He sends in a report beseeching his overseers to set up a meeting with him and when a decidedly reticent Mousa meets him, Yahya laments: “Memories have fused with dreams, with illusions, with facts, so that I no longer know anything.” The irony is that Mousa turns out not to know anything either… By the end of the picture, hunted by operatives of the underworld and repudiated by the law, though perfunctorily intromitted into the “above-world,” Yahya finds himself longing for his life in the Land of Fear, despite its having led him to rape, murder and an evident psychic schism.

Yahya learns from Mousa that he has been living a lie within a lie: the mise en scène is fractured, as is the protagonist's psyche

Yahya learns from Mousa that he has been living a lie within a lie: the mise en scène is fractured, as is the protagonist's psyche

Land of Fear is a rich, relevant picture, despite its allegory and its determinedly embellished, seedy milieu. We all project multiple personae. We act differently at work than we do around our families. We act differently in public than in private. How many times have I wondered how it is that a person could act so respectfully toward a boss that he abhors, while treating with disdain a life partner. How many of us have laughed at a superior’s daft joke, forcing the grin and churning the chuckle. We are all false, to some degree. Land of Fear compels us to confront this falsehood.

Land of Fear is also a luxuriant picture. Its dialogue is streetwise and lucid, its characters complex and cohesive. The story and its characters draw upon Egyptian modern political history—the vicissitudes of the successive regimes of Nasser, Sadat then Mubarak—upon monotheistic legend and upon American crime pictures. Abdel Sayed is not interested in realism; that is not to say that he is not interested in the truth—small t, for Abdel Sayed would intrinsically oppose any notion of Truth.

A subtitle declares the year of a pivotal scene in Land of Fear. The year is 1981, the year Mubarak succeeded Sadat as president. We see Yahya in the back of a luxurious car then we see it turning to park in a row of Mercedes S class sedans, an unmistakable sign of wealth in the Middle East, and we realize that he’s made the grade. Soon, a group of Cairo kingpins are meeting a representative from a non-local syndicate who proposes that they switch from selling hash to coke. He showcases a handheld parcel of boudrah (powder) and declares that it stands to earn a profit margin of 500%, against the 100% that the kingpins realize in selling es-sinf (literally the variety). He adds that the parcel once cut would deliver a return equivalent to a truckload of hash.

Vito Corleone says no to drugs in The Godfather (1972)

Vito Corleone says no to drugs in The Godfather (1972)

Hudhud says no to powder in Land of Fear

Hudhud says no to powder in Land of Fear

Two of the kingpins demur; one named al-Manzalawi earnestly protests, asserting that the two products are not the same, that the authorities would consider him a criminal if he started selling powder. The more vociferous protest, however, is issued by a most memorable movie criminal, one named Hudhud, played to potent poignancy by the marvelous Hamdi Gheith. He tells off the representative, alerting him that unlike himself the rep’s bosses will never know their customers and as such will never have to directly deal with the consequence of poisoning them. Hudhud later invites Yahya to his labyrinthine Old Cario home and confides in him that God has created and as such provides for kingpins like himself, that it is his divine duty to alleviate the struggle of the people by distributing god’s own creation. Hudhud asserts that he has nothing against the authorities, that they too serve a purpose, as do hashish dealers. Gheith imbues his part with an unmistakable sagacity and integrity, despite his criminality, which turns murderous when necessary.

HoopoeLand of Fear conspicuously draws on monotheistic scripture. Yahya’s codename is Adam, after all, a code name of which he learns when invited to a secret meeting wherein he is propositioned to undertake Land of Fear. To a backdrop of a stylized storm he bites into an apple. Hudhud, the wise kingpin, is also Arabic for hoopoe, a bird mentioned in the bible as abominable to eat (Leviticus), perhaps thence informing the Egyptian proverb, “It is not every bird whose flesh is edible” ("مش كل طير اللي يتاكل لحمه"), which may well paraphrase the threat that Hudhud issues to Ragab, the syndicate representative. Then there is Mousa (Arabic for Moses), the postal officer who unsuccessfully attempts to deliver Adam’s letters to his principles, failing to convey messages between creator and created.

HoopoeLand of Fear conspicuously draws on monotheistic scripture. Yahya’s codename is Adam, after all, a code name of which he learns when invited to a secret meeting wherein he is propositioned to undertake Land of Fear. To a backdrop of a stylized storm he bites into an apple. Hudhud, the wise kingpin, is also Arabic for hoopoe, a bird mentioned in the bible as abominable to eat (Leviticus), perhaps thence informing the Egyptian proverb, “It is not every bird whose flesh is edible” ("مش كل طير اللي يتاكل لحمه"), which may well paraphrase the threat that Hudhud issues to Ragab, the syndicate representative. Then there is Mousa (Arabic for Moses), the postal officer who unsuccessfully attempts to deliver Adam’s letters to his principles, failing to convey messages between creator and created.

Cop confronts criminal in Heat (1995)

Cop confronts "criminal" in Land of Fear

Cop confronts "criminal" in Land of Fear

Most potently, however, is the influence of American crime cinema on Land of Fear. The kingpins’ refusal to get with the new and deal in cocaine recalls that of the Don Corelone’s (Marlon Brando) refusal to back Virgil Sollozzo’s (Al Lettieri) investment in smack, because he feels that it would be bad for neighborhoods and would undermine his relationships with politicians. A late scene in Land of Fear, in which Yahya’s nemesis, a competent and incorruptible cop named Omar al-Asyuti asks to meet him in a café, riffs on the central scene involving cop and criminal (played by Al Pacino and Robert De Nero respectively) in Michael Mann’s masterpiece Heat. Most notable, however, is the film’s borrowing from the underrated American crime film Deep Cover, including the mode of the investigative operation and the arch of the undercover protagonist played by Lawrence Fishburn.

Those who scoff at the Land of Fear’s lack of originality must not realize how artistic influence works and must have not come around to reckoning that those who claim utter originality do so because they fear discovery of their fraudulence. All artists borrow; the best reimagine and re-illustrate, as has Abdel Sayed in Land of Fear.

Nevertheless, Land of Fear is not perfect. Makeup design underwhelms. Ahmed Zaki, despite his boyish face is not helped in passing for a 20-some-year-old man. Costume design is even worse. “Could they not corral some bellbottoms and wide lapels to depict action in the 1970s?” I wondered. Against these, however, are a number of standout facets. Beside Ahmed Zaki’s performance, among the best delivered by the actor who many rightly consider the leading Egyptian cinematic actor of his generation, Land of Fear presents us with Hudhud, as fascinating a screen villain as I have ever seen. Locations, from queries to cabarets to opulent villas to Nile delta marshes entrench the polemical state of luxury and decrepitude. The soundtrack, composed by regular Abdel Sayed collaborator Rajih Daoud, what with its tumbling angles and pleading chants, looped and electronically processed, immeasurably enhance the mood of falling and failing.

Abdel Sayed deploys a couple of distinct visual and auditory flourishes, but unlike his wont—and auteur beloved—sequence shots (plan-séquence) here they support the story. In a number of sequences, Abdel Sayed surveys the scene with an overhead shot, as if to deliberately distance audience from action, lest the audience regard what they see as realistic. Abdel Sayed’s interest in asserting allegory is even more pronounced in his blatant use of dissolves, which are rarely used today, but which in Hollywood classic films usually connoted a movement between a character’s lived and remembered states. In Land of Fear, dissolves serve the comingling of reality and memory in the mind of its disillusioned protagonist Yahya (literally meaning to live).

Such visual flourishes are enforced by the echoing of dialogue in pivotal scenes and especially by Yahya’s narration, which guides the film’s audience throughout, a narration which, as in Deep Cover, recalls an idiom of American film noir. Only here, Abdel Sayed has Yahya narrating in formal Arabic (لغة فصحى), unusual in non-historical Egyptian cinema, and not only when Yahya is voicing the letter of his reports. Abdel Sayed is unmistakably positioning the teleological tale in the land of fable, in the land of fear.

I have convinced myself that Daoud Abdel Sayed deserves to take the time he does to work on his films and am delighted to read of an impending conclusion to principal production on his most recent Abnormal Abilities (my translation) ("قدرات غير عادية") (Ma'moun). Yet, I fear for him as I do for all who express critically in Egypt at the moment, considering the alarming, reprehensible crackdown on journalists and activists. Abdel Sayed not only has the right to express as he wishes but should be celebrated for his unshakeable integrity and unmitigated ambition. Abdel Sayed does not wish to become an auteur; he always was one. He does not make independent films. He makes films independently--as independently as a filmmaker can work and live in the land of fear.

Works Cited

Abdel Sayed, Daoud. "Cinematic Censorship of Egyptian Selections." The Full Picture. Lilian Daoud. Cairo, 27 October 2013. Video. <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A_07ItXOCbI>.

Hammad, Suheir. "Letter to anthony (critical resistance)." Hammad, Suheir. Za'atar Diva. New York: Cypher Books, 2005. 67. Document.

"Leviticus." Holy Bible, New International Version. Biblica, 2011. 11:13-19. Document. <http://www.biblegateway.com/passage/?search=Leviticus+11%3A13-19>.

Ma'moun, Asma'. "Daoud Abdel Sayed: I Will not Realease Abnormal Abilities During the Eid Becauuse of a Clamour ." Al-Youm As-Sabi' 14 April 2014. Document. <http://www1.youm7.com/News.asp?NewsID=1611507#.U06Bu_ldWSp>.

Mustafa, Tariq. Coptic Artists ... Integrated with the Strength of Their Talent. 13 March 2010. Document. 10 April 2014. <http://www.masress.com/rosaweekly/44311>.