Al-Kitkat (1991): Soaring above the Doldrums

04-2-2012 | tagged

04-2-2012 | tagged  1991,

1991,  Al-Kitkat,

Al-Kitkat,  Arab cinema,

Arab cinema,  Arab film,

Arab film,  Comedy,

Comedy,  Daoud Abdel Sayed,

Daoud Abdel Sayed,  El-Kitkat,

El-Kitkat,  Ibrahim Aslan,

Ibrahim Aslan,  Mahmoud Abdel Aziz,

Mahmoud Abdel Aziz,  auteur,

auteur,  egyptian,

egyptian,  الكيت كات |

الكيت كات |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Have you ever watched a film that seemed to encourage you to speak with the characters on the screen or with a neighbor, during its watching? There are films that convey to the audience not to concern themselves with plot so much, though plots come attached, but with the companionship and kinship between the characters portrayed. Such films have often been disparagingly dubbed “buddy flicks,” as if there were something embarrassing about enjoying companionship and kinship.

Have you ever watched a film that seemed to encourage you to speak with the characters on the screen or with a neighbor, during its watching? There are films that convey to the audience not to concern themselves with plot so much, though plots come attached, but with the companionship and kinship between the characters portrayed. Such films have often been disparagingly dubbed “buddy flicks,” as if there were something embarrassing about enjoying companionship and kinship.

Films as varied as Renoir’s La Grand Illusion, Hawks’s Rio Bravo, and Spheeris’s Wayne’s World (yes, Wayne’s World) gloriously exemplify such a rhetorical approach, in that they present us with authentic, sincere characters interacting in such a way as not to be in the service of some compulsory plot, but in the service of each other. Yet, these films’ radiance stems from their masterful control of tone, so enrapturing as to irresistibly invite the audience to interact with their characters. Such films also invite repeated viewing, because they are the cinematic equivalent of comfort food. Al-Kitkat is such a film.

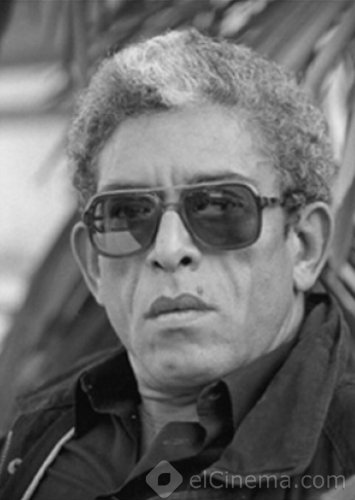

Al-Kitkat (El-Kitkat, الكيت كات) is also notable for being both its auteur director’s most popular film and his best. Daoud Abdel Sayed is one the most accomplished Egyptian directors working today, one whose body of work is arguably rivaled only by Yousri Nasrallah and Mohamed Khan’s. Al-Kitkat is the third of eight films that Abdel Sayed has made, beginning with The Vagabonds in 1985, all of which have I seen. His films, all of whose scripts he has worked on, repeatedly exhibit several bents of their “author”: a potent nostalgia; a love of music and an appreciation for its contribution to film, in both its diagetic and non-diagetic form; an evident adoration of his characters, including of the “villains” among them, and a regard for them that exceeds the demands of plot making; an inclination toward long takes, minutes-long at times; and perhaps most conspicuously his championing of non-conformity that manifests in the depiction of outcasts and rebels, granted, but also obtains in a thoroughgoing depiction of non-conformity as embraced by socially conscious common people who come around to recognizing that the rules have been written to benefit those who’ve written them and, more significantly, that the rules have been written too broadly to mind the unique conditions of the individual.

Daoud Abdel SayedAbdel Sayed’s films to my mind have usually been excellent and have twice approached greatness (the whimsical Land of Dreams, which appropriately became legendary actor Faten Hamama’s cinematic swan song, and the superb crime drama Land of Fear, about which I intend to post). Yet, only al-Kitkat has attained such greatness, due to the superlative contributions of two other personalities involved—Ibrahim Aslan, author of Malik al-Hazin (The Heron, not that one shows up anywhere in the novel. It is perhaps Aslan himself), the novel from which the screenplay was adapted, and Mahmoud Abdel Aziz, who plays Sheikh Husni, the protagonist. Al-Kitkat would showcase the greatest achievements of these three collaborators.

Daoud Abdel SayedAbdel Sayed’s films to my mind have usually been excellent and have twice approached greatness (the whimsical Land of Dreams, which appropriately became legendary actor Faten Hamama’s cinematic swan song, and the superb crime drama Land of Fear, about which I intend to post). Yet, only al-Kitkat has attained such greatness, due to the superlative contributions of two other personalities involved—Ibrahim Aslan, author of Malik al-Hazin (The Heron, not that one shows up anywhere in the novel. It is perhaps Aslan himself), the novel from which the screenplay was adapted, and Mahmoud Abdel Aziz, who plays Sheikh Husni, the protagonist. Al-Kitkat would showcase the greatest achievements of these three collaborators.

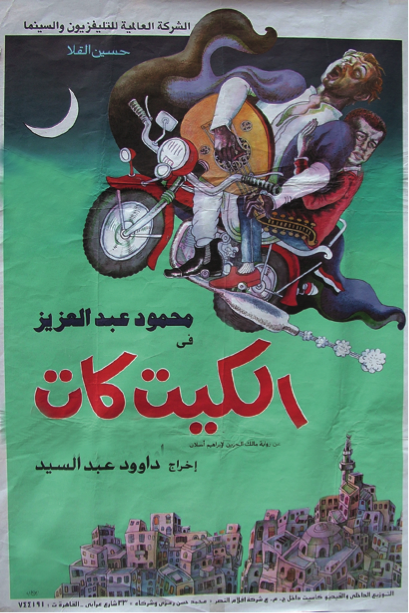

The Heron (1983) is a sprawling novel, which is belied by its unintimidating length of 170 pages or so. Thus, The Heron adapted into screenplay was necessarily condensed (even Altman would have struggled with so many characters and incidents), narratively unified and aptly anchored in the character of a single protagonist—Sheikh Husni. The novel, which took Aslan nearly a decade to write, names tens of characters, progresses by moving ahead and in between a handful or so narrative lines, and seems to distill two centuries in the history of Imbaba district, particularly of its neighborhood dubbed al-Kitkat, which had once been an enormous bar constructed by the locals for land owner Baron Henry Meyer, before it was shut down following the “blessed” revolution ( in 1952) then converted into shops by people who tore into its structure.

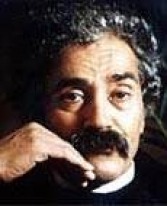

Ibrahim AslanAslan, who passed away at the beginning of this year, published little, over the course of his near half-century-long career. The Heron, his most celebrated work, itself reads as if selected and extracted from a much larger document, which seems confirmed by his having reported that he wrote with an eraser.1 The Heron bombards the reader with names of people and locations, relates events not obviously marked as occurring or remembered, and frequently transitions between subplots, some proving inchoate and all coming to a collective boil as the novel wraps with the assault on al-Kitkat by security forces during the 1977 Bread Riots. Read in 2012, the delicately written and richly detailed story of The Heron turns particularly eerie toward the end as a character examines a protest in Tahrir Square then later collects used teargas canisters inscribed with “Made in the USA.” That the edition of The Heron I had read (in Arabic, though it has been translated into English) had boasted a forward by Suzanne Mubarak only entrenched such eeriness.

Ibrahim AslanAslan, who passed away at the beginning of this year, published little, over the course of his near half-century-long career. The Heron, his most celebrated work, itself reads as if selected and extracted from a much larger document, which seems confirmed by his having reported that he wrote with an eraser.1 The Heron bombards the reader with names of people and locations, relates events not obviously marked as occurring or remembered, and frequently transitions between subplots, some proving inchoate and all coming to a collective boil as the novel wraps with the assault on al-Kitkat by security forces during the 1977 Bread Riots. Read in 2012, the delicately written and richly detailed story of The Heron turns particularly eerie toward the end as a character examines a protest in Tahrir Square then later collects used teargas canisters inscribed with “Made in the USA.” That the edition of The Heron I had read (in Arabic, though it has been translated into English) had boasted a forward by Suzanne Mubarak only entrenched such eeriness.

Mahmoud Abdel Aziz at the time of the film’s making was a star. His rugged European good looks had surely supported his talent in positioning him as a romantic/adventure lead in Egyptian cinema (the obvious favoring of European looks, especially among female leads is a worthy topic of a future entry). Although lacking the gravitas of contemporaries Nour El-Sherif (who had co-starred with Abdel Aziz in Abdel Sayed’s first film The Vagabonds) and Ahmed Zaki, Abdel Aziz over the course of the 1980s exhibited a knack for mischievous humor and for folk music performance, both of which would inform Abdel Aziz’s performance in al-Kitkat, a performance effected with such relish as to suggest that the actor had waited his entire career to play Sheikh Husni in a performance that will likely go down as Abdel Aziz’s career best.

Abdel Aziz’s portrayal of the blind deadbeat appears at first affected, until the viewer realizes that this is not a miscalibration on the part of the actor, but a manifest quality of the character’s. Sheikh Husni is a mischievous operator, who could well owe half the neighborhood money, money of which he manages to make a little on the side by guiding blind people around the district (the blind leading the blind?) He affects and exaggerates because he feels he must to get by. The way he had to sell the house that his father had built, home to his mother and his equally work-averse son, to get by, even though he admits when pressed that he sold it to his drug dealer El-Haram (a nickname meaning “the pyramid”) to support his hashish habit. Despite such failing, rather with its aid, Abdel Aziz imbues his Sheikh Husni with such charisma as to make him irresistible and unforgettable.

Abdel Sayed conjoined the talents of Aslan and Abdel Aziz, along with those of other skilled cast and crew members to craft an entertaining, heartwarming film that is visually and auditorily impressive. The three numbers, featuring Sheik Husni’s singing and oud playing, especially the one in duet with his son, not only entertain the viewer, but also illustrate the joy that music brings to people who populate a world that at times seems set against themselves.

As for the imagery, it is pleasantly surprising to learn that the film had been shot entirely in a studio2. The vividness in detail of the set design and the languorous pacing of the action convince us of the authenticity of milieu and invite us to sympathetically regard the lives of the unsuccessfully working class of al-Kitkat. Two standout sequences illustrate this. One is a still camera, minute long shot that begins with Sheikh Husni and his blind client Sheikh Ubeid in extreme long shot, barely visible behind street vendors and pedestrians, though audible, as they shoot the breeze while ambling toward the camera. Another sequence qualifies as one of the few “pure cinema” sequences I have encountered in commercial Arab cinema. In it, Sheikh Husni convinces the owner of a scooter to permit him to take it for a spin, resulting in an exulting moment that feels like a lifetime, all the more impressive considering the havoc that such a stunt wreaks in al-Kitkat.

As for the imagery, it is pleasantly surprising to learn that the film had been shot entirely in a studio2. The vividness in detail of the set design and the languorous pacing of the action convince us of the authenticity of milieu and invite us to sympathetically regard the lives of the unsuccessfully working class of al-Kitkat. Two standout sequences illustrate this. One is a still camera, minute long shot that begins with Sheikh Husni and his blind client Sheikh Ubeid in extreme long shot, barely visible behind street vendors and pedestrians, though audible, as they shoot the breeze while ambling toward the camera. Another sequence qualifies as one of the few “pure cinema” sequences I have encountered in commercial Arab cinema. In it, Sheikh Husni convinces the owner of a scooter to permit him to take it for a spin, resulting in an exulting moment that feels like a lifetime, all the more impressive considering the havoc that such a stunt wreaks in al-Kitkat.

As I considered my lack of concern for blind Sheikh Husni, joyriding a Vespa in a crowded neighborhood, I realized that it was because I believed what he believed, which was that everything would be alright, as if I were being reassured by an old friend who is much more seeing than given credit for. It is in this good natured, authentic reassurance that al-Kitkat’s distinction is located. Those among us who have seen it and championed it know that whenever in the doldrums, we can pop al-Kitkat in, imagine the sofa a Vespa, pay Sheikh Husni a visit and willingly permit him to drive it, so that, if only for a couple of hours, we may soar above our doldrums.

Works Cited

- Qualey, M. Lynx. "Goodbye Ibrahim Aslan." Egypt Independant. Al-Masry Al-Youm, 1, 8, 2012. Web. 2 Apr. 2012. http://www.egyptindependent.com/node/590166

- Shafik, Viola. Arab Cinema: History and Cultural Identity. Cairo, Egypt: The American University of Cairo Press, 1998. Print.