“Seeing” Rodney King’s Arrest through Barthes’ Three Meanings

02-21-2015 | tagged

02-21-2015 | tagged  Barthes,

Barthes,  Rodney King,

Rodney King,  William Mitchell,

William Mitchell,  police brutality |

police brutality |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |  Email Article |

Email Article | Reading William Mitchell’s classic digital imaging work The Reconfigured Eye, I had not expected to find mention of Rodney King, the single paragraph that it was[i], though I had decided twenty pages earlier to link the operative chapter, “How to Do Things with Pictures” to a disquisition on the Rodney King arrest video. It has not been quite a quarter of a century since King’s fateful arrest on March 3rd, 1991, but then I’ve never been into jubilees.

At the point of referring to the Rodney King arrest video, already Mitchell had cited Barthes’s notion of the press photograph in dialogue within a context, a linguistic one, with at least a title or caption[ii]. I find it likely that Barthes would have thought the same of press motion pictures, analog video for example, such as the edited, broadly TV-broadcast recording of the Rodney King arrest captured by hobbyist photographer George Holliday.

Mitchell himself uses parlance that evokes the legal procedure when discussing photography’s deployment of “larger signifying structures to report the significant facts (or ‘facts’) about states of affairs that are claimed to have existed and events that are claimed to have taken place, and how such reports are used to convince, to create belief, and to command assent.”[iii] Mitchell then goes on to write, “A piece of evidence is a fact with significance in some context, a fact that has been pressed into service, used to support some claim or argument. It serves to tell us about something in the past… Photographs then present facts but are frequently used as evidence.”[iv]

Which leads me back to Barthes, who despite writing about photography throughout his accomplished career, including in his final work Camera Lucida (1980), wrote on film in a single instance of which I know and even then referring only to a film’s stills and not to any “motion” photography: stills from Sergei Eisenstein’s Ivan the Terrible in his 1970 essay The Third Meaning. In this essay, Barthes lays out three levels of semiotic interpretation, tiers of sense making according to functionality: “communication,” “signification” and “signifiance.”[v] I wish to explore these three tiers in the hermeneutic experience of viewing the video of the motorist’s arrest, particularly within the courtroom, in a manner that applies The Third Meaning’s mode of analysis to the motion, instead of to the still, photograph.

Barthes’ first discussed level—or perhaps range is a better description—his first range of interpretation is the one he addresses only in passing in his noted essay, that of “communication.” Here is the interpretation concerned with transference of information. The experience of drawing information from viewing of the video recording of King’s arrest. Information was communicated to viewers in two distinct realms: the public realm, mitigated by press and broadcast (the internet would not have figured in public opinion then), and the realm of the courtroom, which subsumed the goings-on of the public realm since the video had been shown on national TV and discussions about it had taken place for months before the trial had begun.

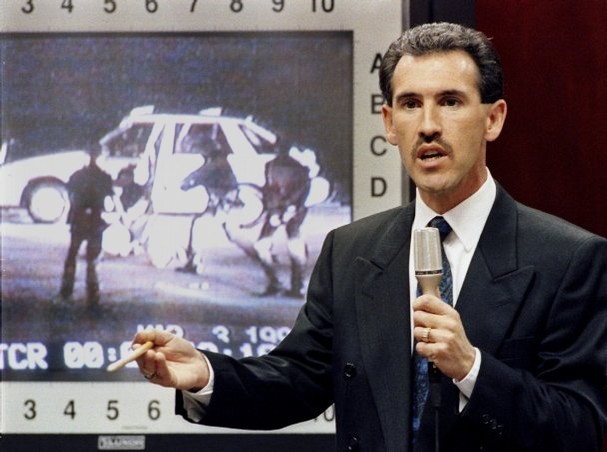

The video of nine minutes and twenty seconds in total[vi] had its first thirteen seconds truncated, including the video’s first three seconds which depicted King rushing at one of the four arresting officers. The video was not consumed in its entirety by most American viewers who saw a minute or two of it (I included, at the time), because news broadcasters opted to broadcast the most graphic segments of it, at a length of sixty-eight seconds. The jury, on the other hand, saw those same 68 seconds, but were persuaded to reconsider the pervasive account of brutal arrest by the 13 seconds noted, excised by the local TV station KTLA to whom photographer Holliday had conveyed his video, because seconds 4-13 were blurry.[vii] In court, expert witness Sargent Charles Duke going through the video frame by frame managed to convince the jury--of ten whites, a Hispanic and an Asian--that Officer Koon was justified in each blow he had administered to King. The jury acquitted the officers of ten of the eleven charges and was hung on the eleventh, concerning only one of the four indicted officers--Powell.

Sergeant Charles Duke, witness for the defense

Barthers’ second range is that of “signification” of what he explains as the “obvious meaning,” the decided and directed symbolism of the image. To mind comes the race and gender of the person undergoing arrest. “Driving while black,” King is dressed in clothes that do not connote “work,” unlike the officers, who are dressed in the regalia of government—of the authorities.

Then there were captions. After all, hardly any words could be made out of the video’s soundtrack, recorded from an apartment’s balcony nearby by an amateur photographer, as a helicopter hovered above the arrest scene. Instead, Sargent Duke narrated the action by explaining the developments as they progressed, one frame at a time. Duke did not describe what he saw on screen, but interpreted for the jury the actions of Officer Koon, based on his own occupational expertise.[viii]

What observers and analysts have missed about the conduct of the trial, however, is precisely Barthes’ third range of meaning—“signifiance.” Barthes describes this as the image’s obtuse meaning: “Indifferent to moral or aesthetic categories (the trivial, the futile, the false, the pastiche), it is on the side of the carnival.”[ix] Here Barthes refers to the disguised or the undeliberately revealing, the truth in the absurd. Several witnesses representing law enforcement testified in the case, all referred to by their occupational title despite wearing civilian clothes, including three of the defendants, two of whom engaged in a narration or explanation of the action in the 81-seconnd segment of Holliday’s video.

Theodore Briseño, one of the four defendant officers

Theodore Briseño, one of the four defendant officers

The TV used was a large CRT set, perhaps even 40 inches in size, but it was of a concave screen variety and placed at a distance of at least several meters from the jury. Moreover, particular components of each frame were pointed to by what may be called a baton, that used by the police as well as a different a pointer of a baton, such as the sort that could be used in a classroom.

Sergeant Stacey Koon, another of the four defendants

Terry White, African American prosecutor in King’s case described the jury polemically: “They were people who believe there is this 'thin blue line' separating law-abiding citizens from the jungle--the criminal element.”[x] During the trial, the judge had permitted the inclusion into evidence of a remark made by Laurence Powell, one of the officers on trial, transmitted from his squad car, earlier on the day of King’s arrest, in which he had likened domestic trouble among blacks to the film Gorillas in the Mist[xi]. A gorilla in the jungle is not likely to wield a baton, but a police officer could wield one with authority, regardless of its shape or intent of use.

[i] Mitchell, William. The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-photographic Era. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1994. 212

[ii] Ibid. 191

[iii] Ibid

[iv] Ibid. 192

[v] Barthes, Roland. "The Third Meaning: Reasearch Notes on Some Eisenstien Stills." Barthes, Roland. Image, Music, Text. New York: Hill and Wang, 1977. 52-54.

[vi] The disagreement about the length of the video is curious: The ascribed length is eight minutes in a Los Angeles Times article. ("The Other Beating." Los Angeles Times 19 February 2006. http://articles.latimes.com/2006/feb/19/magazine/tm-holiday8.) Only that five years later, the same publication described the video as nine minutes long. (Rubin, Joel, Andrew Blankstein and Scott Gold. "Twenty years after the beating of Rodney King, the LAPD is a changed operation." Los Angeles Times 3 March 2011. http://articles.latimes.com/2011/mar/03/local/la-me-king-video-20110301), as did by Time, following year. (Gray, Madison. "Rodney King, Whose Police Beating Led to Los Angeles Riots, Dies at 47." Time 17 June 2012. http://newsfeed.time.com/2012/06/17/rodney-king-whose-brutal-police-beating-sparked-the-deadliest-riot-in-u-s-history-dies-at-47/). These errors are intriguing since a (near) exact length was reported much earlier, in 1993, in The Philadelphia Inquirer (Clark, Robin. "Life After Taping The King Beating Hasn't Always Been Easy He Has Been Hounded By The Media, Cursed By Strangers. His Wife Returned To Argentina." The Philedelphia Inquirer 19 April 1993. http://articles.philly.com/1993-04-18/news/25983219_1_george-holliday-police-officers-king-video) much closer to the length I have clocked in watching a version recorder from a camera pointing to a TV playback of the video, as posted on YouTube (Weinstein, Henry. "After the Riots: The Search for Answers." Los Angeles Times 8 May 1992. http://articles.latimes.com/1992-05-08/news/mn-1894_1_king-case), and the duration (9 min 20 sec) noted by the most extensive work on the King affair by Lou Cannon in Official Negligence: How Rodney King and the Riots Changed Los Angeles and the LAPD.

[vii] Cannon, Lou. Official Negligence: How Rodney King and the Riots Changed Los Angeles and the LAPD. Boulder: Westview Press, 1999. 23

[viii] "Expert Testifies Officers' Beating Of Motorist Complied With Policy." New York Times 20 March 1993. http://www.nytimes.com/1993/03/20/us/expert-testifies-officers-beating-of-motorist-complied-with-policy.html

[ix] Barthes, Roland. "The Third Meaning: Reasearch Notes on Some Eisenstien Stills." Barthes, Roland. Image, Music, Text. New York: Hill and Wang, 1977. 55.

[x] Weinstein, Henry. "After the Riots: The Search for Answers." Los Angeles TImes 8 May 1992. http://articles.latimes.com/1992-05-08/news/mn-1894_1_king-case

[xi] "Judge Says Remarks on 'Gorillas' May Be Cited in Trial on Beating." New York Times 12 June 1991. http://www.nytimes.com/1991/06/12/us/judge-says-remarks-on-gorillas-may-be-cited-in-trial-on-beating.html