Entrepreneurship in a State of Flux: Egypt’s Silent Cinema and Its Transition to Synchronized Sound, 1896-1934

06-9-2020 | tagged

06-9-2020 | tagged  Egypitianzing,

Egypitianzing,  Egypt,

Egypt,  Egyptianess,

Egyptianess,  early cinema,

early cinema,  film history,

film history,  media studies,

media studies,  national cinema,

national cinema,  nationalism,

nationalism,  nationalist cinema,

nationalist cinema,  silent cinema,

silent cinema,  synhronized sound cinema |

synhronized sound cinema |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |  Email Article |

Email Article | Readers may know that over the last six years I have been at some PhD business, which has consumed most of my energy. Punctuating my work thereof is a dissertation study whose abstract I paste below. I would be happy and ready to share this dissertation upon request:

Entrepreneurship in a State of Flux: Egypt’s Silent Cinema and Its Transition to Synchronized Sound, 1896-1934

This is a work of cultural history, mainly because it had to be, because I realized that such a history would most enable my writing a dissertation length work about a cultural industry scarcely documented in primary sources and restrictively written about since. As for my conceiving the early cinema on the Nile as a cultural industry, that was because I found the conception of Egyptian cinema presumptive. Egypt gained its status as a (nominally) independent modern nation-state in 1922, so that for much of the cinema’s early existence in Egypt it and the people who interacted with it were governed according to systems in good part delineated centuries earlier. Moreover, at no time during this study was the most dominant governmental power in Egypt headed by “native” Egyptians.

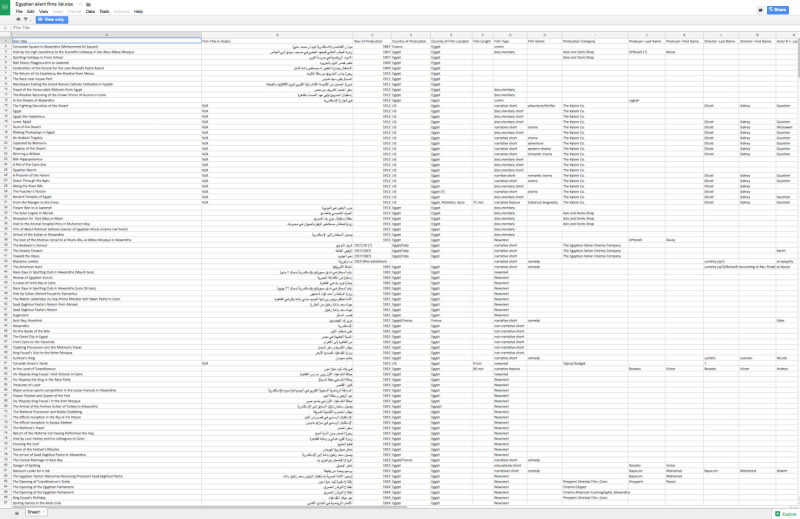

Egyptian cinema foreclosed people and institutions qualified as non-Egyptian. As it turned out, the most influential, most capitalized practitioners in Egypt’s cinema into the mid-1930s were not of Egyptian origin, though some may have 'naturalized.' I also learned that of the totality of activity we may qualify as cinema, most was not in production of films, but in their exhibition, an industrial subsector that directly engaged far more people than did filmmaking in Egypt’s urban and rural locals. As I learned, exhibition was industrially linked to distribution by the most powerful institutions of what I came to describe as the early cinema industry, 1896-

1934. Egyptian cinema had methodologically restricted studies past, produced within Egypt and without, in delimiting the seemingly non-Egyptian, whether people or institutions. The term had also relatively promoted the study of textual production within the cinema, often as a facet of cultural creation and commodification overseen if not undertaken by the state. A study of the early Egyptian cinema would be limited materially and restrictive conceptually. I would study the cinema in Egypt as a collective activity that organized overtime and was propelled by exchange among people and institutions, Egyptian or not, regardless of points of origination or conclusion to instances or patterns of exchange.

By examining complex power relations of the political economy of Egypt’s early cinema industry I move to justify the noted methodological shift declared in the title of the first chapter. “How the Cinema in Egypt Egyptianized” is framed as a reflexive investigative journey into suchmodern history of relevant power relations centered in Egypt and affecting its cinema. I interrogate the concept of national cinema in the second chapter and bespeak Egyptianizing (tamassur), two addresses on which I elaborate theoretically and historically. I follow this discussion with two illustrative case studies of Egyptianizing of cineastes and their institutions in tow, from the operative era. The third chapter attends to the intersecting histories of film pioneer Mohammed Bayoumi and the Misr Company for Acting and Cinema, later Studio Misr, the first bona fide film studio in the Middle East, as led by Tal`at Harb. Both men avowed nationalism and both contributed to the development of the cinema in Egypt in the name of the nation. Chapter three integrates analysis of Bayoumi’s nonfiction films, among those survived silent productions noted, an examination that situates their texts within their cultural and historical contexts. The final chapter makes the case for the significance of the interaction between the theater and cinema industries in Egypt in the studied era. It does so by charting the generic interlinks between stage and screen, specific as they had been to Egypt: (melo)drama, comedy, and singing. In keeping with previous chapters that have instrumentally elaborated on domains of cinematic activity other than production—distribution, exhibition, and press—productions and practitioners are linked to audiences, playhouses, and movie houses. This final chapter also complements or augments discussions from the earlier chapters in each of its three genre-bound segments. In the end, this work is intended to critically assess nationalism as it relates to the cinema, while drawing attention to a cinema underserved by media histories.