Having attended elementary and secondary public schools in Saudi Arabia until the age of fourteen, I became keenly aware of the Wahhabi[1] repudiation of realistic pictographic representation of life—animal and particularly human life—though not plant life. I could not have foretold the attention that “animation” in such discrepant forms as pre-Islamic Assyrian statues and polished internet ISIS propaganda videos would attract a quarter of a century later.

To be sure, the Saudi government permitted depiction of animal and human life forms on state television, in the press, and in third party publications produced in the country or imported. Censorship was enforced strictly, so that broadcast programs were edited to remove whatever provoked in the minimum the conservative sensibility of the autocratic, theocratic government. Aside from the provocation of varied content, a stricter interpretation of Islamic doctrine than that imposed by the government had it that depiction of animal and particularly human life was forbidden outright. Such a view was pervasive enough that I have found drawings I made in early elementary school wherein a line crosses the necks of animals and humans, certainly in response to a teacher’s request, to undercut a presumed intent in drawing to depict realistically. Years later, classmates and I would be admonished by religious teachers that watching TV was forbidden, regardless of content, because it depicted lifeforms.

By the time I had left Saudi, I was confused about the religious acceptability of depiction, because I had noticed the variety of opinions and interpretations regarding. What seemed contradictory was that more realistic depictions were considered more flagrant, so that sculpting humans was more egregious from a religious practice standpoint than two-dimensional depiction, while representation by hand, such as in painting or drawing, was considered more flagrant than “mechanical” depiction such as by camera. In recent years, we have witnessed the modern era’s most extreme advocate for Islam not merely condone video depiction, but practice it instrumentally, for propaganda, including the depiction of ISIS members destroying iconographic sculptures that the group considers idolatrous.

ISIS could indeed be described as the New Iconoclasts, who similar to the original Byzantine Iconoclasts referred to by Baudrillard in Simulacra and Simulation, would appear to practice an uncompromising form of rejection of representation of not only divinity but of god’s creation. In fact, reprimands I heard in Saudi school in my youth, drawn from the Saudi government’s adopted ideology of Wahhabi Islam, which borrows much from the scholarship of 11th century theologian Ibn Taymiyyah, as does the ideology of ISIS[2], sounds near identical to the description of the sentiments expressed by Christians across broad territories, critical of devotional depiction in images, prior to the Byzantine Iconoclasm against cultish devotional practices in the 8th century.[3]

As is told in the Qur’an, the Prophet Muhammad ordered that the idols in the vicinity of the Ka’ba be destroyed upon his conquest of his hometown of Mecca with his followers, in 630 CE. ISIS is continuing this tradition a millennium and a half later[4], so as to seem far more outmoded than the Prophet and his followers had been, though I suspect that Jean Baudrillard has suggested the motivation behind iconoclasm in both instances:

But what becomes of the divinity when it reveals itself in icons, when it is multiplied in simulacra? Does it remain the supreme authority, simply incarnated in images as a visible theology? Or is it volatilized into simulacra which alone deploy their pomp and power of fascination - the visible machinery of icons being substituted for the pure and intelligible Idea of God? This is precisely what was feared by the Iconoclasts, whose millennial quarrel is still with us today. Their rage to destroy images rose precisely because they sensed this omnipotence of simulacra, this facility they have of erasing God from the consciousnesses of people, and the overwhelming, destructive truth which they suggest: that ultimately there has never been any God; that only simulacra exist; indeed that God himself has only ever been his own simulacrum. Had they been able to believe that images only occulted or masked the Platonic idea of God, there would have been no reason to destroy them. One can live with the idea of a distorted truth. But their metaphysical despair came from the idea that the images concealed nothing at all, and that in fact they were not images, such as the original model would have made them, but actually perfect simulacra forever radiant with their own fascination. But this death of the divine referential has to be exorcised at all cost.[5]

ISIS has demolished the remains of the 2,000 year-old city of Hatra, in fact, including structures not depicting any life form, having already assaulted the 3000 year-old remains of the city of Nemrud and a museum of antiquity in Mosul, the largest city currently under ISIS’s control[6]. All the while, ISIS had deployed video, arguably more lifelike than an antique statute in that it depicts movement and sound, whose style and content had been greatly informed by narrative Hollywood action films.[7] As such, ISIS has determined to assault creative works of indigenous origin, which have negligible influence on current ideological lives of people in the area, as it borrows a foreign art form and coopts creative works imported from an entity which it opposes vehemently—the United States. How could such an approach stand as congruous with the group’s doctrine, which has been central to its recruitment practices?[8]

The explanation, I reckon, is twofold and is contained in Walter Benjamin’s seminal essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Firstly, sculpture, such as of pre-Islamic civilizations of the Middle East, and painting, such as that which I undertook in art class in my childhood, involve the hand in creation of the work—throughout. Whereas photography involves the manipulation of apparatuses that perform the work on behalf of the hand, arguably a comparatively indirect practice of “creation.” As Benjamin famously qualified, “For the first time in the process of pictorial reproduction, photography freed the hand of the most important artistic functions which henceforth devolved only upon the eye looking into a lens.”[9] Secondly, photography in all of its forms, differs from painting, sculpture and other pre-industrial pictographic art forms in that photographic images reproduced and re-disseminated ad infinitum lack what ruins evidently possess, what Benjamin describes as the “aura” of non-reproducible arts works.[10]

What will ISIS make of virtual reality technologies—looming as they are, if one were to follow the announcements and maneuvers by the likes of Google and Facebook[11]—and their holographic accruement, one might ask? I predict that ISIS would adopt them, because of their potential utility in persuasion, a practical concern of the group, and because of the technology’s “indirect” creation, as far as its human users are concerned—an apparent, though arguably false, removal of such creation from human agency. Indeed, we may not look forward to ISIS continuing to adopt new media technologies in an effort to assert its governmentality upon not only the people under its territorial control, but Muslims far and wide.

[1] Wahhabism (المذهب الوهابي) was not a commonly purveyed term describing the particular brand of Islamic theology in the Saudi Arabia of the 80s, from my experience. Rather, the theology was presented as the correct interpretation of Islam with hardly a qualification.

[2] Ideological links between Wahhabism and Ibn Taymiyyah, as well as between ISIS and Ibn Taymiyyah are well established. See ”You Can't Understand ISIS If You Don't Know the History of Wahhabism in Saudi Arabia,” by Alastair Cook, a quarter-century operative of MI6 and Middle East political writer, a background that would have me distrust him, were it not for the perspicacity of his work. June 29, 2014. <http://www.huffingtonpost.com/alastair-crooke/isis-wahhabism-saudi-arabia_b_5717157.html> and “The other side of Ibn Taymiyya – on the occasion of the political ascent of Salafis and Islamists,” by Abdel Hakim Ajhar of al-Quds al-Arabi. December 14, 2011. < http://arabist.net/blog/2011/12/20/in-translation-will-the-real-ibn-taymiyya-please-stand-up.html>

[3] “In the age before iconoclasm, therefore, certain basic positions had been staked out by both the attackers and the defenders of images. The former said that God was a purely spiritual being who could not be depicted. Depictions, in any event, were made of vile matter which was unsuited to the divine essence and also encouraged the worship of material creation. Creation itself, moreover, was God’s work alone. People should not, in creating images, presume to share in God’s work. Images were idols, or so very much like them as to make no difference. Finally, God revealed himself in words, not in pictures.” Thomas F. X. Noble. Images, Iconoclasm, and the Carolingians. University of Pennsylvania Press. Philadelphia. 2009. 27

[4] As is the Saudi government of ruins dating back to the dawn of Islam—see “The Destruction of Mecca.” Ziauddin Sardar. New York Times. Sep 30, 2014. < http://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/01/opinion/the-destruction-of-mecca.html?ref=todayspaper&_r=0>

[5] Simulacra and Simulation (originally published in French in 1981). The University of Michigan Press. Ann Arbor. 1994. 169

[6] See “Iraq Says Islamic State Militants Raze Ancient Hatra City.” Ahmed Rasheed and Isabel Coles. Mar 7, 2015. < http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/03/07/us-mideast-crisis-iraq-hatra-idUSKBN0M30GR20150307>

[7] See “Islamic State and Its Increasingly Sophisticated Cinema of Terror.” Jeffrey Fleishman. Los Angeles Times. Feb 26, 2015. < http://www.latimes.com/entertainment/movies/la-et-mn-ca-isis-video-horror-20150301-story.html#page=1>

[8] See “The Secret World of ISIS Training Camps—Ruled by Sacred Texts and the Sword.” Hassan Hassan. The Observer. Jan 24, 2015. < http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/jan/25/inside-isis-training-camps>

[9] The renowned remark is found under “I”

[10] ISIS videos may lack taste in the extreme, but that does not preclude their artistry. See Benjamin under “III”

[11] See “Google’s Android to Take on Facebook in Virtual Reality.” Rolfe Winkler. Wall Street Journal. Mar 6, 2015. < http://www.wsj.com/articles/googles-android-to-take-on-facebook-in-virtual-reality-1425684553>

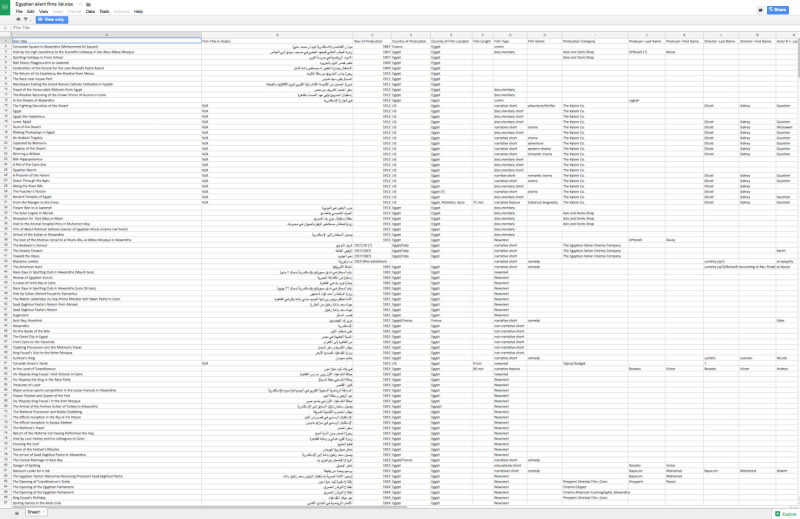

11-21-2015 | tagged

11-21-2015 | tagged  Egyptian cinema,

Egyptian cinema,  Egyptian film,

Egyptian film,  Egyptian silent movies,

Egyptian silent movies,  list of Egyptian movies,

list of Egyptian movies,  silent cinema |

silent cinema |  1 Comment |

1 Comment |  Email Article |

Email Article |