The Attack (2012): Polished, Inchoate and False

07-29-2013 | tagged

07-29-2013 | tagged  Ali Suliman,

Ali Suliman,  Israel,

Israel,  Lebanon,

Lebanon,  Yasmina Khadra,

Yasmina Khadra,  Ziad Doueiri,

Ziad Doueiri,  banned,

banned,  controversial,

controversial,  matryrdom,

matryrdom,  suicide,

suicide,  terrorism,

terrorism,  الصدمه |

الصدمه |  Post a Comment |

Post a Comment |  Email Article |

Email Article | Humans are not the only animal to carry out suicide attacks I came to learn in researching for this review. A termite species found in French New Guinea sends off its old to carry out suicide attacks, deploying poison reserves that they will have accumulated over a lifetime. Curiously, the researcher who uncovered this behavior characterized it as altruistic.1

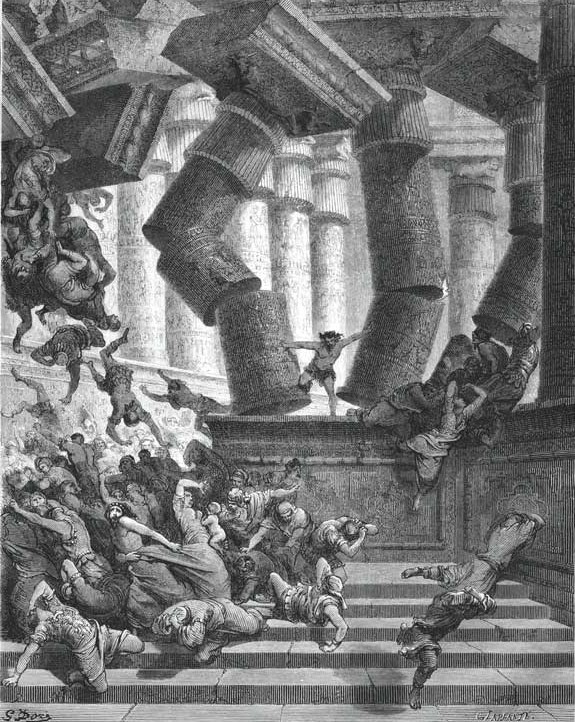

Samson destroys himself and his enemiesAs have theologians of one Samson’s suicide attack. Of the many violent crimes mentioned in the bible I was startled to learn that suicide attack is one. The attacker in question is the Israelite judge Samson who, after a lifetime of resisting the Philistines on behalf of his people, asks God to empower himself to kill those Philistines who had been summoned to regard the vanquished warrior (not realizing that despite Samson’s blindness his great strength had returned): “Samson said, ‘Let me die with the Philistines!’ Then he pushed with all his might, and down came the temple on the rulers and all the people in it. Thus he killed many more when he died than while he lived.”2

Samson destroys himself and his enemiesAs have theologians of one Samson’s suicide attack. Of the many violent crimes mentioned in the bible I was startled to learn that suicide attack is one. The attacker in question is the Israelite judge Samson who, after a lifetime of resisting the Philistines on behalf of his people, asks God to empower himself to kill those Philistines who had been summoned to regard the vanquished warrior (not realizing that despite Samson’s blindness his great strength had returned): “Samson said, ‘Let me die with the Philistines!’ Then he pushed with all his might, and down came the temple on the rulers and all the people in it. Thus he killed many more when he died than while he lived.”2

Indeed, though most suicide attacks in modern times have been carried out by Muslims, non-Muslims have carried them out or prepared for them, responding principally to Nationalist ideologies: Kamukaze (nationalist though literally meaning “god’s wind”) fighters and Tamil Tiger militants (check out the superb Indian film The Terrorist.) As far as European native and settler societies are concerned, it has come to surface that Churchill had designated a secret group named the Auxiliary Unit (otherwise known as the Scallywags), which was to carry out a variety of militant acts of resistance in the event of a German occupation of Britain—a unit of4000 volunteer civilians. Tom Skyes, who had campaigned for official recognition of the Auxiliary Unit stated about its members: “Many of these veterans were in reserved occupations and could not join the regular Forces… But when the call came, they did not hesitate to join what would have been a suicide mission to confront the enemy.”3 Indeed, the most probing investigation4 into the motivation behind contemporary suicide bombing has found it weakly linked to religious fundamentalism, Islamic or otherwise.5 Rather, opposition to occupation and a desire to gain strategic advantage over it has described almost all such attacks, as has been proved by another comprehensive study conducted since.6 There is strategic advantage to not having to execute an exit plan, since an exit is not part of the plan.

A time existed not long ago when suicide attack was the commonly used term in Palestinian circles, though I do not now think that its gradual replacement with martyrdom bombing reflects the increasing religiosity among Palestinians, but a rejection of the connoted self-centeredness of suicide versus the connoted collectiveness of martyrdom: Those who commit suicide die for themselves, whereas those who commit martyrdom die for their people. Yet, whereas suicide is an objective term (as is Bush’s homicide attack, but homicide is confusing, because attacks that may involve homicide may well not involve suicide), martyrdom is subjective. Martyrdom’s meaning resides in perception of the act, not in the very act of self and enemy destruction for the sake of sustaining the cause of one’s own people.

Subjective is not to say ethnically or religiously restrictive, for martyrdom has been a term of use in a variety of religious traditions of various peoples. It was curious to encounter a resistance to describing Samson’s act mentioned above as suicide within the Judeo-Christian tradition7, which views suicide as immoral as the Islamic has, in favor of … you’ve guessed it—martyrdom. Not surprising, considering that Samson is the only character treated as a “keeper of the faith” among the several whose acts of suicide populate the bible.8

Palestinian militants who died in battle or during attacks, long before the first sucide attack of modern times, carried out in 19829, were called martyrs as well, including secularists and communists. Nor does a majority Palestinian Muslims support suicide attacks “in the name of Islam,” according to a recent PEW poll, though a higher percentage of Palestinian Muslims do than in any other predominantly Muslim country.10 That Afghanistan polled a scratch second to Palestine on the question of the occasional justifiability of suicide bombings is telling.

Occupation engenders acute indignity, an indignity that starting in the early 80s, though not since 200811, has persuaded fewer than 200 Palestinians to volunteer to seek terminal revenge. One such person was 29-year-old Palestinian lawyer Hanadi Jaradat, who detonated the explosives belt strapped to her waist in a restaurant in Haifa, in 2003, killing twenty people and wounding many others. Her family reported afterward that her decision was motivated by the Israeli Defense Forces’ (IDF) killing of her brother and her fiancé, as well as for Israeli crimes of murder and land expropriation in the West Bank.12Jaradat was also in all likelihood the person who inspired the character of Sihem, author Yasmina Khadra’s Samson in his own piece of fiction The Attack, published in 2005. In the bestselling novel, Sihem is the secular, seemingly adjusted and integrated spouse of the novel’s protagonist, Palestinian hotshot surgeon Amin Jaafari, with whom she has shared a life in Tel Aviv for over a decade. Sihem blows herself up early in the novel, also in a restaurant.

Amin’s world is pulverized. Beyond smiting grief, he must deal with the ramifications of living in Israel as the spouse of a Palestinian who blew herself up in a restaurant full of Jewish kids. Further, Amin feels zealously impelled to investigate how the woman he had thought he knew so well, a secular-humanist, could bring herself to commit such a horrific act, not having betrayed her intention to himself in the least. Amin is determined to uncover who had taken the love of his life from him and persuaded her to betray her legacy with himself, a legacy that she had helped build. In his quest, he traces a couple of clues to Bethlehem, Nazareth and Jenin. (Nablus appropriately stands in for Bethlehem in the film, Nazareth is referred to, and Jenin is dispensed with.)

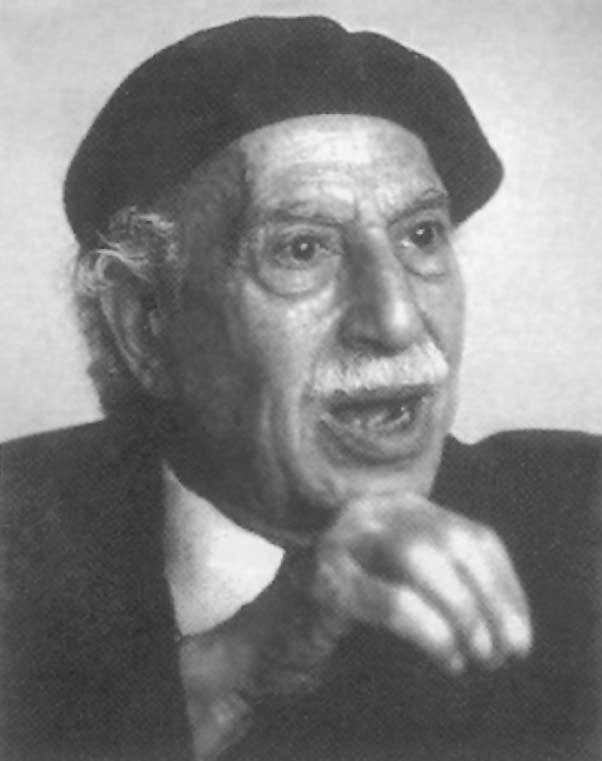

Yasmina Khadra (AKA Mohammed Moulessehoul)The Attack, the novel, is at its best when mining its protagonist’s psyche, the psyche that Dr. Amin Jaafari has for years tamed, following formative years in the West Bank whose memory he has utilitarianly quarantined. Yasmina Khadra (nom de plume of Algerian Mohammed Moulessehoul, who immigrated to France with his spouse—suprise—Yasmina Khadra) does two things indicative of an adept modern storyteller: He injects his characters with evident humanity, which is a better way of saying that he cares about his characters. Secondly, Khadra manages to bring the story to a fulfilling end-start point, without its seeming as if it were heading there.

Yasmina Khadra (AKA Mohammed Moulessehoul)The Attack, the novel, is at its best when mining its protagonist’s psyche, the psyche that Dr. Amin Jaafari has for years tamed, following formative years in the West Bank whose memory he has utilitarianly quarantined. Yasmina Khadra (nom de plume of Algerian Mohammed Moulessehoul, who immigrated to France with his spouse—suprise—Yasmina Khadra) does two things indicative of an adept modern storyteller: He injects his characters with evident humanity, which is a better way of saying that he cares about his characters. Secondly, Khadra manages to bring the story to a fulfilling end-start point, without its seeming as if it were heading there.

Regrettably, Khadra’s assiduous insistence that his novel honor its characters’ impulses and intentions, its pretense to secure a “balance” (existing subjectively, not objectively) comes off as stilted, especially when relying on baroque imagery and metaphors of a bygone era, which serve to soften the blow of the compunction suffered by his liberal humanist non-Arab readers’ sympathizing with a suicidal Muslim martyr. It’s as iff Khadra determined to broker insight into the most macabre realm of Muslim civilization to the secular humanist West and was rewarded for his delicacy and sagaciousness under topical duress with recognition and abundant sales.

Additionally, Khadra’s efforts fall short in a number of ways that a seasoned writer’s shouldn’t. I developed a wee concern when I saw the spelling of Sihem’s name. Palestinians would pronounce the name Siham. However, I all but forgot about this quibble when I came upon the principle example of The Attack’s major lapse. Amin is a naturalized Palestinian Israeli, but there is no such human. At first, I thought Khadra had meant a Palestinian Israeli, one born as a minority citizen of Israel, but soon enough I realized that Khadra intended him as a Palestinian born in the West Bank who had managed by attending medical school in Israel to acquire Israeli citizenship, as highly skilled professional may in more developed countries (MDC). Well, it could not happen. It could not have even happened through Amin’s having married an Israeli citzen, which Sihem is.13

Throughout The Attack, Khadra describes the severed territories as far more open to each other’s denizens than they really are. Israelis travel into the West Bank and even live there (no, not just within settlements) and Palestinian militants posing as businessmen travel through Israel “proper” freely—flagrantly fantastical. Khadra, despite his extensive sociological research, has made a few indicative assumptions. Thereby Khadra has cast his complex, sympathetic characters in a fairly contrived, hazily miserable world, persuaded perhaps by the postulate that such a vivification would meet the conception of the “Palestinian/Israeli conflict” held by the secular humanist Western European audience (as well as institutional supporters) that the novel would have to win over first.

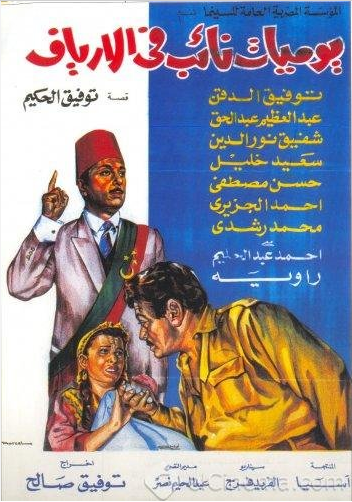

Ziad DoueiriZiad Doueiri’s interpretation of the novel is also hazily vivid, most appropriately in the first 20 minutes or so, the lead-up to Amin’s identification of Siham’s (her name’s pronunciation corrected) body. This intro is rendered with a deftness and polish that belie the film’s relatively meager $1.5 million budget.

Ziad DoueiriZiad Doueiri’s interpretation of the novel is also hazily vivid, most appropriately in the first 20 minutes or so, the lead-up to Amin’s identification of Siham’s (her name’s pronunciation corrected) body. This intro is rendered with a deftness and polish that belie the film’s relatively meager $1.5 million budget.

At the film’s center, in the role of Amin is one of the best Arab screen actors working today—Ali Suliman (who himself curiously played the abdicating suicide martyr in Hany Abu-Asad’s Paradise Now). Suliman, like all excellent actors, has great command over him movement and stillness. Wherein The Last Friday Suliman was seen fidgeting, hesitating and tilting, herein we find him a man depleted by anguish and indignity, so that even in rising to admonish or to accuse we see a person summing up energy reserves from all corners of his body. Suliman is a treat to watch, as is Uri Gavriel as Captain Moshe, whose scenes of interrogating Amin are among the best.

Ali Suliman as Dr. Amin JaafariDoueiri, who has written the screenplay with his spouse Joelle Touma, insists on secularizing the character and motivation of the Palestinian suicide bomber, which must be why Doueiri and Touma convert Khadra’s Sihem, the secular Muslim martyr, to Christianity, as does the screenwriting pair a young Muslim militant leader, who in the film becomes a young, vaguely militant priest.

Ali Suliman as Dr. Amin JaafariDoueiri, who has written the screenplay with his spouse Joelle Touma, insists on secularizing the character and motivation of the Palestinian suicide bomber, which must be why Doueiri and Touma convert Khadra’s Sihem, the secular Muslim martyr, to Christianity, as does the screenwriting pair a young Muslim militant leader, who in the film becomes a young, vaguely militant priest.

What the writing pair does not do is to fix the naturalization and freedom of movement problems that mar the novel. And though this would upset the knowing, i.e. Palestinians, it does not the drama. What does undercut the film’s dramatic effect markedly, however, is the dispensation of the lyrical, elegiac conclusion that takes place in Jenin in the novel, amidst the ruin and carnage of an Israeli military incursion, in favor of a muddled, intrinsic finis. A single vestige of the novel’s near closing Jenin chapter is Amin’s coming upon, in Nablus, a site of an unremarkable, unindicative concrete demolition, replete with a graffiti verse “Ground Zero.”

As such, the film eventuates having concretely presented little, in dialogue or in imagery, of the oppression and injustice that has driven Palestinians to justify the murder of civilians, having restricted its explanation of the motivation behind such self-enemy annihilation to the following: on the Israeli side as a false historical narrative of Palestinian bonkers-bomber motivation, presented as probing, objective assessment on the part of two radio news show hosts. On the Palestinian side, such motivation is obliquely explained by two religious figures, distrusted a priori by secular humanists.

Too many well-funded, high profile films centering on Arab/Muslim suicidal martyrdom have been made I reckon, including three last year alone: beside The Attack, Horses of God (by far the best of the bunch) fictionalizes the actual coordinated suicide attacks in Casablanca, Morocco in 2003 and Inch’Allah culminates with a Palestinian martyrdom attack that waxes insipid by sensationalism. After all, Morocco has not seen a suicide attack since the noted and Palestine has not since 2008. Thus, what we have are films that feign boldness to tackle a most difficult subject, while engaging a discourse based on outmoded events. Suicide attacks carried out by Muslims in the last year have mainly occurred in Iraq, Pakistan and in Afghanistan. Most have been sectarian attacks against Muslims and/or have targeted occupation, particularly, US and collaborator targets. If a film about suicide martyrdom is to be made at all then it ought to be a gritty, realist, timely work, a Battle of Algiers for our day.

Note: The title The Attack has been translated into Arabic, in the cases of book and film, curiously as as-Sadmah الصدمه, which translates better as The Shock and is a term usually more internally directed than, say, al-hajmah الهجمة—a decision informed by target audience sensitivities perhaps?

- Cormier, Zoe. "Termites explode to defend their colonies." Nature. Nature Publishing Co., 26 July 2012. Web. 26 July 2013. <http://www.nature.com/news/termites-explode-to-defend-their-colonies-1.11074>.

- New International Version. Biblica, 2013. Web. 25 July 2013. <http://www.biblica.com/bibles/chapter/?verse=Judges+16&version=niv>. Judg. 16:30

- Elliott, Valerie. "Honoured at Last: Churchill's Secret Guerillas Who Were Poised to Execute Senior British Figures if There Was a Risk of Them Helping the Germans After Nazi Invasion." Mail Online. Associated Newspapers, 30 Mar. 2013. Web. 26 July 2013. <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2301720/Churchills-secret-guerillas-poised-execute-senior-British-figures-risk-helping-Germans-Nazi-invasion.html>.

- King, Oliver. "News Blog: What really motivates suicide bombers?" The Guardian. Guardian News and Media, 11 Aug. 2006. Web. 26 July 2013. <http://www.guardian.co.uk/news/blog/2006/aug/11/suicidebombers>.

- Pape, Roberet A. Dying to Win: The Strategic Advantage of Suicide Terrorism. New York: Random House, 2005. Print. pp. 3

- Harris, Rachel S. "Samson's Suicide: Death and the Hebrew Literary Canon." Israel Studies 17.3(2012): 67-91. EBSCO. Web. 28 July 2013. pp. 67-69

- Hassan, Riaz. "What Motivates the Suicide Bombers?" Yale Global Online 3 Sept. 2009: n. pag. Web. 28 July 2013. <http://yaleglobal.yale.edu/content/what-motivates-suicide-bombers-0>.

- O'Mathuna, Donal P. "But the Bible Doesn't Say They Were Wrong to Commit Suicide, Does it?" Suicide: A Christian Response : Five Crucial Considerations for Choosing Life. Ed. Timothy J. Demy and Gary P. Stewert. Grand Rapids: Kregel, 1998. 349-66. Print. pp. 361

- Chicago Project on Security and Terrorism. "Suicide Attack Database." Suicide Attack Database. U of Chicago, 14 Oct. 2011. Web. 28 July 2013. <http://cpost.uchicago.edu/search.php?noresults=1>.

- A Rising Tide Lifts Mood in the Developing World: Sharp Decline in Support for Suicide Bombing in Muslim Countries. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, 2007. Pew Research Global Attitudes Project. Web. 28 July 2013. <http://www.pewglobal.org/2007/07/24/a-rising-tide-lifts-mood-in-the-developing-world/>.

- See # 9

- Burns, John F. "The Mideast Turmoil: The Attacker; Bomber Left Her Family with a Smile and a Lie." New York Times [New York] 7 Oct. 2003, World: n. pag. The New York Times. Web. 28 July 2013. <http://www.nytimes.com/2003/10/07/world/the-mideast-turmoil-the-attacker-bomber-left-her-family-with-a-smile-and-a-lie.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm>.

- "Israel Upholds Citizenship Bar for Palestinian Spouses." News: Middle East. BBC, 12 Jan. 2012. Web. 28 July 2013. <http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-16526469>.