“Tell me, Khalil, what did the king’s daughter do?”

“The king’s daughter fled with him and they went to another kingdom”

Hussein KamalI wonder what it would have been like for a cinephile to have lived in Cairo in the early 1970s, to have marveled at what director Hussein Kamal had accomplished in under a decade and to have mused over what would be in store for him. It would have seemed likely that he would bring to himself and by association to his national cinema unprecedented esteem and recognition. Egyptian cinema would indeed garner recognition in the years to come, though mostly for the work of Kamal’s senior Yousef Shaheen. Kamal’s own output since would not match the blazing success of his early films, most of which still stand among the most notable works of the Egyptian cinema.

Hussein KamalI wonder what it would have been like for a cinephile to have lived in Cairo in the early 1970s, to have marveled at what director Hussein Kamal had accomplished in under a decade and to have mused over what would be in store for him. It would have seemed likely that he would bring to himself and by association to his national cinema unprecedented esteem and recognition. Egyptian cinema would indeed garner recognition in the years to come, though mostly for the work of Kamal’s senior Yousef Shaheen. Kamal’s own output since would not match the blazing success of his early films, most of which still stand among the most notable works of the Egyptian cinema.

Kamal’s first film The Impossible (1965)—nay, its first shot, a tracking shot of the troubled protagonist walking a shopping district pavement —declared his talent. The Impossible was the first in a trilogy that would come to represent his first period as filmmaker, a trilogy whose unsettling stories illustrated in resplendent black and white photography and complex sound design. To call Kamal’s fourth film a departure would be an understatement. My Father above the Tree (1969) was a lurid, extravagant revue in vivid color that set a standard for the genre that the Egyptian cinema has arguably not reached since1. Kamal would make several more notable films, including the highly regarded satire Chatter on the Nile (1970) and family melodrama Emipre of “M” (1972).

It has been argued that Hussein Kamal’s films lost much or their luster once he had been compelled to abandon black and white photography for color2. (The iconoclastic, almost entirely black and white burlesque Chatter on the Nile hints at Kamal’s disgruntlement with the imposed transition to color, in boasting a single scene in color wherein a music video director lauds the color treatment of a comically cruddy song and dance production.) Others have contended that Kamal’s career descent had to do with his opting for decidedly commercial projects3, perhaps having realized the rewards of the colossal commercial success of My Father above the Tree. Having watched films of Kamal’s from the 1980s I found myself bemoaning that though Kamal’s knack had persisted, his virtuosity had considerably depleted. The singular success of the latter part of his career would be in his direction of a hilarious theatrical rendition of Raya and Sakina.

The Postman (1968)Not that I grieve Kamal’s career. Quite the contrary: I would be delighted to review at least half a dozen of his films and think that his oeuvre rivals those of the greats of Egyptian cinema Salah Abu Seif, Youseff Chahine and Henri Barakat. It is his second film, however, that left my head hanging with humility at its end. It is The Postman (1968, البوسطجي) whose scenes for days replayed as I drove, through one eye, as the other was relegated to minding the road.

The Postman (1968)Not that I grieve Kamal’s career. Quite the contrary: I would be delighted to review at least half a dozen of his films and think that his oeuvre rivals those of the greats of Egyptian cinema Salah Abu Seif, Youseff Chahine and Henri Barakat. It is his second film, however, that left my head hanging with humility at its end. It is The Postman (1968, البوسطجي) whose scenes for days replayed as I drove, through one eye, as the other was relegated to minding the road.

The Postman is based on a novella by the same name, written by Yahya Haqqi, one of Egypt’s most admired literary figures of the last century. Haqqi’s influence on Egyptian culture realized primarily in his having edited the state owned and by now legendary journal Al-Majallah, during most of the 1960s. (The journal, whose publication had ceased by the Sadat regime, along with other publications, in what came to be known as the campaign to “put out cultural lanterns,” has relaunched recently in the wake of the Egyptian Revolution.4) The Postman is one of four works of Haqqi’s to have been adapted for film and one of two to whose adaptations he had contributed.

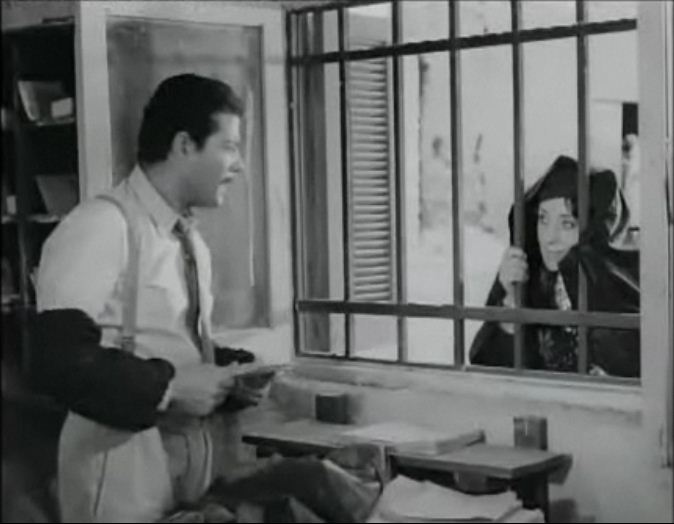

The Postman (1968)The Postman tells of the experience of ‘Abbas a postal worker from Cairo who is assigned to a post in Koum Annahl (literally “heap of bees”) a village in the Central Si’eed. ‘Abbas is soon appalled with the provinciality of the village, with the vulgarity of its population and with the dilapidations of his own meager quarters that he rents exorbitantly, to his own mind, from the mayor. As ‘Abbas’s despair mounts, he resorts to mollifying the hateful quiet of rural nights with the drink, which then expectedly distorts his temperament in the days following, eventuating in his unclosing letters and peeping into the lives of others, desperate for a semblance of community.

The Postman (1968)The Postman tells of the experience of ‘Abbas a postal worker from Cairo who is assigned to a post in Koum Annahl (literally “heap of bees”) a village in the Central Si’eed. ‘Abbas is soon appalled with the provinciality of the village, with the vulgarity of its population and with the dilapidations of his own meager quarters that he rents exorbitantly, to his own mind, from the mayor. As ‘Abbas’s despair mounts, he resorts to mollifying the hateful quiet of rural nights with the drink, which then expectedly distorts his temperament in the days following, eventuating in his unclosing letters and peeping into the lives of others, desperate for a semblance of community.

The Postman (1968)A particular regular exchange interests ‘Abbas, that between Khalil and Jamilah, an exchange whose peculiarity and intrigue beguile him into an ongoing voyeurism of their epistolary romance. As it were, ‘Abbas underestimates the consequence of having interpolated himself. He soon learns of Jamilah’s desperation, of her unplanned pregnancy. He might have managed to assuage a conscience guilty over his not having moved to help her, only that he mistakenly stamps an opened letter from Khalil, one that he had read with great anticipation, while in the office, instead of waiting to read it at home in the evening, as usual. ‘Abbas, unable to come up with a way to conceal or remove the stamp on the letter makes a decision that proves fateful, a decision that would ultimately implicate him in an unmitigated tragedy.

The Postman (1968)A particular regular exchange interests ‘Abbas, that between Khalil and Jamilah, an exchange whose peculiarity and intrigue beguile him into an ongoing voyeurism of their epistolary romance. As it were, ‘Abbas underestimates the consequence of having interpolated himself. He soon learns of Jamilah’s desperation, of her unplanned pregnancy. He might have managed to assuage a conscience guilty over his not having moved to help her, only that he mistakenly stamps an opened letter from Khalil, one that he had read with great anticipation, while in the office, instead of waiting to read it at home in the evening, as usual. ‘Abbas, unable to come up with a way to conceal or remove the stamp on the letter makes a decision that proves fateful, a decision that would ultimately implicate him in an unmitigated tragedy.

Yahya HaqqiThe novella’s elegant, meticulous prose conveys what struck me as a detached familiarity with its milieu. I would later learn what explained this. Haqqi, long aware of his non-Egyptian ethnicity (Turkish and Albanian lineage) urbane and ambitious as he was, had been compelled to take up a legal post in Manfulout in Asyout province, where he spent two years that must have proven challenging, but whose experience would figure mightily in his writing, including in The Postaman5. Haqqi by his own testament absorbed all that was Egypt throughout his life, a bent which coupled with his feelings of displacement while in his rural post must have contributed to the noted detached familiarity.

Yahya HaqqiThe novella’s elegant, meticulous prose conveys what struck me as a detached familiarity with its milieu. I would later learn what explained this. Haqqi, long aware of his non-Egyptian ethnicity (Turkish and Albanian lineage) urbane and ambitious as he was, had been compelled to take up a legal post in Manfulout in Asyout province, where he spent two years that must have proven challenging, but whose experience would figure mightily in his writing, including in The Postaman5. Haqqi by his own testament absorbed all that was Egypt throughout his life, a bent which coupled with his feelings of displacement while in his rural post must have contributed to the noted detached familiarity.

Whereas in the novella Haqqi seems at pains to subtly disinvolve, his screenplay is at pains to contain its fury. The screenplay accommodatingly expands on the novella in ways that suggest Kamal’s influence. The story is made linear in its narrative, dispensing with the flashback story telling by ‘Abbas in the novella, which aids in the steadily accelerating tempo to the drama. More significantly, the screenplay incorporates a subplot wherein Jamilah’s father rapes the maid (who doesn’t exist in the novel). Jamilah’s mother, instead of castigating her husband, arranges for the victim to be taken away by her family, under the pretext that she had behaved shamefully, knowing that her accusation against the maid would near certainly subject her to another round of severe victimization.

The Postman (1968)Kamal in the first decade of his career exhibited a marked interest in women’s struggles and not only as victims of the oppression within the systems that men have created. We Do not Plant Thorns (1970) and Empire of “M” enabled their top billed stars, Shadyah and Faten Hamama respectively, to deliver performances that became standouts of their careers. Female characters in The Impossible, in A Thing of Fear (1969) and in the mentioned Emipre of “M” strike me as some of the most complex and willful in classic Egyptian cinema. It is also notable that Kamal worked regularly with legendary editor of Egyptian cinema Rashidah Abdussalam, including on all films of his mentioned in this review. Kamal also worked with screenwriters Kawthar Haikal and once, on The Postman, with Dunya Al-Baba.

The Postman (1968)Kamal in the first decade of his career exhibited a marked interest in women’s struggles and not only as victims of the oppression within the systems that men have created. We Do not Plant Thorns (1970) and Empire of “M” enabled their top billed stars, Shadyah and Faten Hamama respectively, to deliver performances that became standouts of their careers. Female characters in The Impossible, in A Thing of Fear (1969) and in the mentioned Emipre of “M” strike me as some of the most complex and willful in classic Egyptian cinema. It is also notable that Kamal worked regularly with legendary editor of Egyptian cinema Rashidah Abdussalam, including on all films of his mentioned in this review. Kamal also worked with screenwriters Kawthar Haikal and once, on The Postman, with Dunya Al-Baba.

The Postman (1968)The Postman’s screenplay is not the sole well crafted component, for the film is a tour de force. The acting is credible and precise throughout. The casting of Shukri Sarhan to play ‘Abbas comes off as particularly apt. Sarhan’s enduring strength as an actor was his manifest sense of dignity, a trait that serves The Postman in that the audience is convinced that ‘Abbas is a victim himself, a victim of economic and social need, that he had once been a well-adjusted, functional member of society. The location, not far from Cairo6, with its uneven clay laden landscape, palms and mud houses suggests the misery that an urbanite would experience living in Koum an-Nahl. And editing by Rashidah Abdussalam propels the steadily rising anxiety, especially in the crosscutting between scenes involving ‘Abbas and Jamilah.

The Postman (1968)The Postman’s screenplay is not the sole well crafted component, for the film is a tour de force. The acting is credible and precise throughout. The casting of Shukri Sarhan to play ‘Abbas comes off as particularly apt. Sarhan’s enduring strength as an actor was his manifest sense of dignity, a trait that serves The Postman in that the audience is convinced that ‘Abbas is a victim himself, a victim of economic and social need, that he had once been a well-adjusted, functional member of society. The location, not far from Cairo6, with its uneven clay laden landscape, palms and mud houses suggests the misery that an urbanite would experience living in Koum an-Nahl. And editing by Rashidah Abdussalam propels the steadily rising anxiety, especially in the crosscutting between scenes involving ‘Abbas and Jamilah.

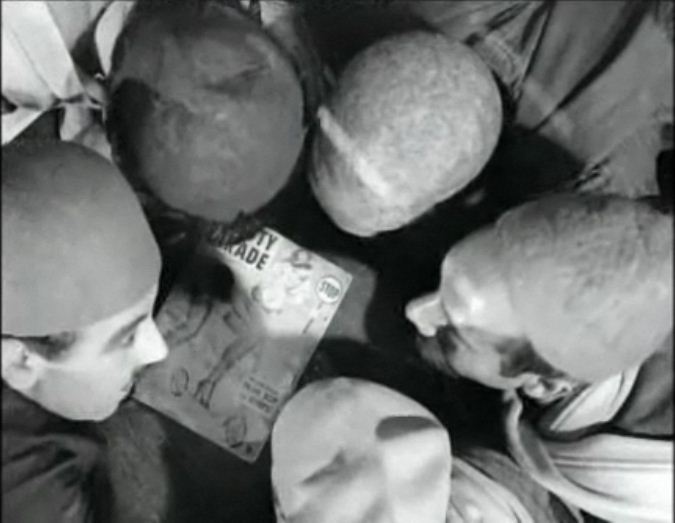

The Postman (1968)It is the compositional scheme and audio design of the film that smite and stamp, however. The Postman’s photographic composition is mostly conventional in the first half of the film, with occasional flourishes that suggest a filmmaker making his restraint known, foreshadowing the tumult to come. As ‘Abbas’s and Jamilah’s (as well as Khalil’s, though mostly through his letters) disaffections begin to mount, the photography and sound design become more expressive and more evocative. Unusual camera angles and stylized mis-en-scene alert us to the topsy-turvy world that the principle characters have come to inhabit, while a looping, echoing, mournful mantra, in Jamilah’s voice, quoting from a fairytale that Khalil had earlier recounted punctuates the pain with the ellipses of ruin: “in another kingdom.”

The Postman (1968)It is the compositional scheme and audio design of the film that smite and stamp, however. The Postman’s photographic composition is mostly conventional in the first half of the film, with occasional flourishes that suggest a filmmaker making his restraint known, foreshadowing the tumult to come. As ‘Abbas’s and Jamilah’s (as well as Khalil’s, though mostly through his letters) disaffections begin to mount, the photography and sound design become more expressive and more evocative. Unusual camera angles and stylized mis-en-scene alert us to the topsy-turvy world that the principle characters have come to inhabit, while a looping, echoing, mournful mantra, in Jamilah’s voice, quoting from a fairytale that Khalil had earlier recounted punctuates the pain with the ellipses of ruin: “in another kingdom.”

Breaking the Waves (1996)And then there’s the final shot, a shot for the books (spoiler alert!) I readily recalled the final shot from Breaking the Waves, Lars Von Tier’s masterpiece. Like The Postman, Breaking the Waves told the tale of a woman who is sacrificed because she had dared to love according to her own impulses. The final shot of Breaking the Waves depicts bells sounding in the heavens, in acknowledgement of such sacrifice. (Curiously, the finale in the novella, which I read after watching the film, has the bell of Koum Annahl’s small church announce Jamilah’s death. The film does not indicate the religious background of her family—Coptic—for then concerns about potential offense7)

Breaking the Waves (1996)And then there’s the final shot, a shot for the books (spoiler alert!) I readily recalled the final shot from Breaking the Waves, Lars Von Tier’s masterpiece. Like The Postman, Breaking the Waves told the tale of a woman who is sacrificed because she had dared to love according to her own impulses. The final shot of Breaking the Waves depicts bells sounding in the heavens, in acknowledgement of such sacrifice. (Curiously, the finale in the novella, which I read after watching the film, has the bell of Koum Annahl’s small church announce Jamilah’s death. The film does not indicate the religious background of her family—Coptic—for then concerns about potential offense7)

The Postman (1968)As evocative as the last shot in Breaking the Waves is, The Postman’s last betters it. Arriving on the scene to find Jamilah having been stabbed to death by her father, ‘Abbas loses his bearings. Reaching into his satchel, he extracts letters that he flings into the air in anguish, as if to protest the futility of human agency against seemingly fateful injustice. He continues to hurl the letters as he passes by the camera and out of the frame, so that the letters momentarily thereafter appear as if to drop from the sky, as if God, rejecting ‘Abbas’s fatalism, has sent letters of protest to the people of Koum Annahl, indicting all of complicity in the unconscionable murder—thesis then antithesis manifest in a single, lingering, heart piercing shot. The Postman is among the finest works to ever come out of the Egyptian cinema.

The Postman (1968)As evocative as the last shot in Breaking the Waves is, The Postman’s last betters it. Arriving on the scene to find Jamilah having been stabbed to death by her father, ‘Abbas loses his bearings. Reaching into his satchel, he extracts letters that he flings into the air in anguish, as if to protest the futility of human agency against seemingly fateful injustice. He continues to hurl the letters as he passes by the camera and out of the frame, so that the letters momentarily thereafter appear as if to drop from the sky, as if God, rejecting ‘Abbas’s fatalism, has sent letters of protest to the people of Koum Annahl, indicting all of complicity in the unconscionable murder—thesis then antithesis manifest in a single, lingering, heart piercing shot. The Postman is among the finest works to ever come out of the Egyptian cinema.

The Postman (1968)

The Postman (1968)

* My Father above the Tree and Chatter on the Nile are available in the US through Arab Film Distribution.

Works Cited:

1. Kamal, Hussein. "Episode 22: Special Discussion with Hussein Kamal" (in Arabic) Interview by Ammar Ashsherei'i. An Evening with Sherei'i. Dream TV. 22 Sept. 2011. YouTube. Web. 4 June 2012. <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XA4D62VxXKY>.

2. Assabban, Rafiq. Hussein Kamal: Lover of the Impossible (in Arabic). Cairo: The Cultural Development Fund, 1997. Digital Assets Repository. Web. 4 June 2012. <http://dar.bibalex.org/webpages/mainpage.jsf?BibID=28951>.

3. Hassan, Mahir. The Passing of Director Hussein Kamal(in Arabic). Al-Masry Al-Youm, n.d. Web. 4 June 2012. <http://today.almasryalyoum.com/article2.aspx?ArticleID=291428&IssueID=2084>.

4. Ali, Sa'd. "Return of Egyptian Cultural Magazine Al-Majallah after an Absence of 40 Years (in Arabic)." Reuters. Thomson Reuters Corporate, n.d. Web. 4 June 2012. <http://today.almasryalyoum.com/article2.aspx?ArticleID=291428&IssueID=2084>.

5. "Egyptian Figures: Yahya Haqqi (in Arabic)." Egyptian State Information Service. N.p., n.d. Web. 4 June 2012. <http://www.sis.gov.eg/VR/figures/arabic/html/3p.htm>.

6. See reference # 2.

7. See reference # 2.

11-26-2012 | tagged

11-26-2012 | tagged  Arab cinema,

Arab cinema,  Arab film,

Arab film,  DTFF,

DTFF,  Doha Film Institute,

Doha Film Institute,  Doha Tribeca Film Festival,

Doha Tribeca Film Festival,  Qatar |

Qatar |  1 Comment |

1 Comment |  Email Article |

Email Article |  Photo credit: Doha Film Institute

Photo credit: Doha Film Institute Museum of Islamic Art. Photo credit: riy

Museum of Islamic Art. Photo credit: riy Souq Waqef. Photo credit: Jan Smith

Souq Waqef. Photo credit: Jan Smith Sony Open-Air Cinema. Photo credit: Ayman Itani

Sony Open-Air Cinema. Photo credit: Ayman Itani Katara. Photo credit: Karen Blumberg Ultimately, it was my encounters with young DTFF volunteers and guest service providers that left the deepest impression. One morning, I was heading to Katara for a meeting and thought to catch the festival shuttle bus. As I boarded, I asked the driver about going there and was told that it would take an hour. “That’s too long,” I responded, before turning to see a teenage boy, in festival T-shirt and badge, who had followed with “That’s too late for me too.” The transportation coordinator at this station (like most, in his early twenties), upon checking my credentials, availed me a car within the festival’s transportation fleet. When the car arrived, I asked the transportation coordinator if it would be OK if the teen came along, which he appreciated, as did my new companion.

Katara. Photo credit: Karen Blumberg Ultimately, it was my encounters with young DTFF volunteers and guest service providers that left the deepest impression. One morning, I was heading to Katara for a meeting and thought to catch the festival shuttle bus. As I boarded, I asked the driver about going there and was told that it would take an hour. “That’s too long,” I responded, before turning to see a teenage boy, in festival T-shirt and badge, who had followed with “That’s too late for me too.” The transportation coordinator at this station (like most, in his early twenties), upon checking my credentials, availed me a car within the festival’s transportation fleet. When the car arrived, I asked the transportation coordinator if it would be OK if the teen came along, which he appreciated, as did my new companion.